This post is by Ron Berger, Chief Academic Officer for Expeditionary Learning.

What would student work look like if it met educational standards, beautifully? What would students sound like when explaining their ideas if it was clear that they had mastered a standard? Would teachers, parents, or the students themselves know how to tell if their work demonstrated the understanding or skill required by the standard?

We spend a great deal of time in this country debating about educational standards, but I am not sure we have a clear idea of what those standards look like. I am not talking about the written description of student skills and understandings you might see on the Common Core website. I am talking about what it would look like if students actually met those standards well--with depth, integrity, and imagination.

The current national discourse about new standards--Common Core and similar state standards--is not about the potential of standards to create great student work and thinking. We are debating instead about the politics of state or federal control; about the tests that will supposedly measure the outcomes of these standards; and about who will be blamed if those tests come out poorly. The most important conversation--what we hope students will know and be able to do, and what that will actually look like if we succeed--is not the focus of discussion in most media, policy meetings, districts or schools.

Every state, whether a Common Core adopter or not, agrees that for college, career, and life readiness, educational standards need to be elevated. We need to prioritize higher order thinking, problem solving, independence, and creativity by engaging students with more challenging tasks. But what does this mean? What does “higher order thinking” look like? Without clear images to inspire and guide us, we spend our time arguing about mandates and accountability, instead of focusing on the goal for all of this change--giving students the vision and skills to do excellent work.

What is missing is clear: models. When young athletes work hard at their sport, they watch older students, Olympians, and professionals and imprint that vision in their hearts and minds. Unfortunately, when young students are engaged in academic work in school--creating a scientific report, persuasive essay, geometric proof, or architectural design--they typically have no idea of what would constitute excellence. They have no inspiration, no provocation, and no vision. We give students written assessment rubrics, but absent models of excellence, those rubrics are just a bunch of words. Picture the difference between reading a rubric of proficient play in soccer, and watching an Olympic soccer game.

But models alone are not enough. We need to analyze models together and discuss and debate the criteria for excellence. We need a vision of what standards actually look like so we know what we are aiming for. Unlike the frustrating, circular discussions about the political sides of standards, discussions about the quality of student work intended by standards can move us forward.

For twenty-five years I have worked with my colleagues at Expeditionary Learning and the Harvard Graduate School of Education to collect, analyze, archive, and curate exemplary student work, and then use that work to improve teaching and learning. My colleague Steve Seidel and I teach a course at Harvard focused entirely on the importance of looking closely at student work to understand standards.

For most of the last twenty-five years, I dragged around a giant black rolling suitcase filled with hard copies of student work models to schools and meetings. I still sometimes drag that suitcase with me, because there is nothing really that compares to holding a piece of beautiful student work in your hands. But thankfully that work also now lives online as an open educational resource in The Center for Student Work where it can be explored, discussed and downloaded to use with students and teachers. You can access that collection here. You can also view videos that demonstrate exactly how beautiful work can meet Common Core standards, such as this one.

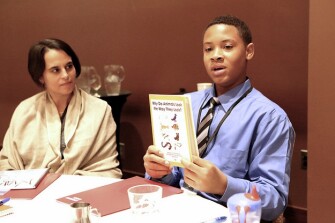

Whether working with students, teachers, educational leaders, or policy makers, one thing has been consistent and striking: the quality of conversation is totally different when student work is in front of us. For example, educators may discuss, theoretically, what high quality writing could look like for a first grade student or high school junior, and debate the meaning of the written standards for each. But everything changes when we look at brilliant writing from a first grader or an eleventh grader. Our understanding of the standards change, and our understanding of the dimensions of excellence is transformed. It’s an entirely new and more powerful conversation.

We invite you to join us in this conversation. We welcome your ideas and contributions. If you have student work you would be proud to share, consider submitting exemplary student project work or writing. Join conversation threads in the Center and contribute your ideas and questions to the discussion. Suggest resources that can help other educators. Most importantly, consider using the collections and resources in the Center to deepen and improve your own work, and let us know what you are learning, what you suggest, and how we can better support your work.

Help us elevate the national conversation about standards from a singular focus on accountability to an exploration of what standards can actually look like if students meet them with depth, integrity, and imagination.