This post is by Sam Dyson, Director, Hive Chicago Learning Network, Mozilla; @samueledyson

Knowing and understanding are different. On the road to deeper learning, you sometimes find that you’ve gained knowledge while losing understanding. The nature of unlearning reshapes the “learning curve” and our expectations of how knowledge and understanding grow over time.

My own “Aha!” moment about the nature of knowing and understanding came in one of my most enduring experiences in ten years as a physics teacher. Before performing a momentum demonstration with two small carts on a collision track, I asked my students to predict what they thought would happen when the two carts collided, and to justify their predictions. Having done so, one young woman was so surprised by what actually happened when the carts collided that she proclaimed aloud, “I don’t believe it!” as if to say, “That thing I just saw with my own eyes is so far outside of what I expected that I completely reject it!” Or “I know what I saw, but I don’t understand it.”

The inability to connect a new piece of information with the world as we already know it--this is a classic problem of the unlearning that is required for deeper learning. Deep learning often involves a period of understanding less than we did at the start. Any student of physics knows this. The reason physics is hard to learn is not because it’s so fundamentally complex. In fact, its principles are deceptively simple. The true challenge is that the idealized principles of textbook physics so often contradict what we “know” from a lifetime of real-world experiences. Learning physics is hard because what we think we already understand is so very hard to unlearn.

This idea is one I first encountered at the Harvard Graduate School of Education as a Masters student. The film A Private Universe taught me to engage student’s privately held ideas with respect, referring to them as preconceptions (prior knowledge), not merely misconceptions (wrong ideas). In my physics classroom, my revelation was that if I was going to teach for understanding, I would have to learn how to engage what my students actually believed--what they thought they already understood.

Deeper learning requires connecting old and new knowledge in initially unfamiliar ways. While knowledge is an indicator of what information we have access to, understanding indicates what connections we are able to make between one bit of knowledge and another. According to Understanding by Design by Wiggins and McTighe, “Misunderstanding is not ignorance, therefore. It is the mapping of a working idea in a plausible but incorrect way in a new situation.”

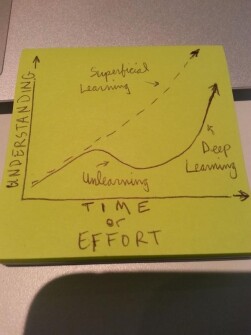

That distinction between knowing and understanding makes for a learning curve that looks more like this sketch (which I initially shared in this tweet reflecting on the topic of deeper learning).

Think of the dashed curve as knowledge, and the solid curve as understanding. As in the case of the physics demonstration, it’s possible to acquire more information (e.g. the knowledge of a new but unexpected observation) while not yet being able to meaningfully connect it to things you already know.

The apparent of paradox of deeper learning is that you can grow to know more at precisely the same moment that you understand less.

As Wiggins and McTighe put it, “Paradoxically you have to have knowledge and the ability to transfer [incorrectly] in order to misunderstand things. Thus evidence of misunderstanding is incredibly valuable to teachers, not a mere mistake to be corrected.”

This ability to make connections is so central to deep learning that it reshapes our expectations of what learning should look like. The u-shaped learning curve above is more than a novel idea. It has also been seen in research on student preconceptions in astronomy. If a learner’s enthusiasm and understanding are linked, this IDEO graph Jal Mehta shared in his post on unlearning might suggest that the process of learning and unlearning is a repeated cycle, not just a singular event.

Supporting this kind of learning requires a shift away from defining teaching as the transfer of information and toward teaching as the design and facilitation of (un)learning experiences. This shift prompts questions like:

- What deep beliefs will my students have to unlearn before they can make any sense of this new content?

- What powerful experiences will make these new connections most likely?

- How do we design spaces where youth feel safe and supported to be vulnerable to learning and unlearning as they forge new connections?

- What is the role of youth interests in deepening engagement and supporting the ability to make connections from one interest to the next?

No longer in the physics classroom, I’m now exploring new contexts for deeper learning. At Mozilla we are working to establish citywide professional learning communities--Hive Learning Networks--in which applying principle of connected learning to explore the role of youth engagement and interests. These efforts leverage the power of technology to enable more connections between otherwise separate domains of learning. Our aspirations for youth are greater equity and access to deeper learning experiences for more youth and for the adults who serve them.

Interested to learn more? Consider joining the active community of researchers and practitioners at the 2015 Digital Media and Learning Conference--Equity By Design, June 11-13, as we work together to build more contexts for deeper learning.