This post is by Corey Clark, 7th Grade Humanities teacher, High Tech Middle North County.

Is my house worth $11,000 more with a Caucasian owner? Not necessarily, but possibly.

Our 7th grade class at High Tech Middle North County engaged in a project this year titled “Home Sweet Home?” This project is part of our class focus on balancing the social scales. We are looking into multiple social injustices such as gender inequality, ageism, perception of beauty, and most recently, race. This particular project challenged our students to examine the dark past of our country’s segregated history and manipulative housing practices. Students were asked to delve into the issue of gentrification (the process of renewal and rebuilding deteriorating areas that often displaces poorer residents), white flight (the move of white city dwellers to the suburbs to avoid more heterogeneous neighborhoods), redlining (the legal segregation of neighborhoods according to race), and racial steering (the modern practice of realtors showing particular houses to clients depending on their ethnicity). Our students were beginning a voyage into a project focused on deeper learning that asked them to collaborate to pose difficult questions on real issues of equity in the world around them. While researching these topics, students immersed themselves in one of the darkest times in American history, the 1900’s fight for civil rights.

Students used a realty database to find their dream homes. They filed through hundreds of listings filled with pictures of vacation homes with resort-worthy pools, beach front properties, acres of land, and outlandish price tags that soared above and beyond seven figures. After our students constructed their American Dream, they took the zip codes of their dream homes and inserted them into a statistics database highlighting their chosen community’s racial demographics, education levels, income disparity, and crime statistics. The mood of the room fell silent as dreams shattered and gave rise to nightmares. Our seemingly united family became instantly segregated when it became evident that even our hopes and aspirations have limitations. It was as if particular students had more helium in the balloons that they had placed their dreams in, and others were forced to realize that their culture or race didn’t belong.

A concerned student reflected on this activity with a sense of confusion and clarity. I can vividly remember him sharing, “I’m seen differently. I’m not seen the same as some of the students seated around me, and it isn’t fair that I will have a more difficult time making my dream a reality. I hate that I am supposed to celebrate all the progress we’ve made. I’m still not equal; that’s not okay.” Our conversation concluded with a question of why was it fair for the American Dream to be held at greater distances for those with different backgrounds and experiences. It became obvious that we in America may have eliminated redlining with the Fair Housing Act of 1968, but the residual effects are still very much alive. As median home prices rise, so does the frequency of homogeneous neighborhoods. Our students began to see invisible signs from a Jim Crow Era staked in the front lawns of the most prestigious zip codes.

The realization that something from our past has lived on was a sickening experience for many of us, but we encouraged each other to push deeper. Is it possible that we can see the residual effects of redlining and segregation in our own neighborhoods?

The question was simple, but to begin answering it would be incredibly costly. As a teacher, I decided to offer my home as the social laboratory for our project. We would invite almost sixty students into my home to stage it in two very different ways, reflecting two very distinct cultures and then have it valued by two different appraisers that were completely oblivious to the project.

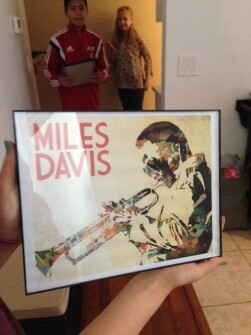

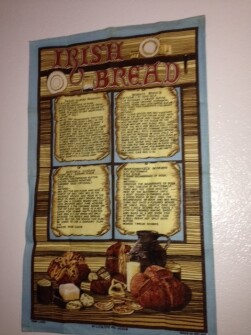

The first step was to take two family volunteers of different races to supply us with information about their culture, interests, and of course, their family pictures. We started with an African-American family whose culture and interests resided in Louisiana. We then constructed the second family whose culture identified with Ireland. Needless to say, the two families appeared very different on the outside. As we staged the home, filling its hallways and walls with family photos and culturally relevant images, our expectations became clouded. Class conversations began to rise. What it would mean if one version of the house was appraised higher than the other? What would that say about our sense of progress since the Civil Rights era? We were uncertain of what we were hoping to discover.

When each staging was complete, the internal components of my home looked well designed, but made it undeniably clear as to the different race and culture of the two respective families. In each case, we contacted two certified home appraisers nearby who had no idea that their appraisal would be part of a project. Neither one had ever met me personally. The only visual connection the appraiser would have to the home’s owner would be found around the home in its decorations and family photos. Our students were filled with curiosity while awaiting the official reports. We discussed what different findings would mean and how scientific experiments create conclusions while social experiments create conversations. Because people are so different, and it is truly impossible to make a social experiment conclusive, our goal is to present findings worthy of difficult, often taboo, conversations. Deeper learning, the type of learning we strive for with our students, challenges them to grapple with difficult issues that don’t have easy answers, in safe spaces.

Eventually, the morning came when both reports were complete and my teaching partner, Kristen Voss, and I were able to share the appraisals. The home belonging to the African-American family was appraised at $389,000; however, with the Irish-American owner, the appraisal arrived at a value of $400,000. The question that immediately rung out from an emotional student sitting toward the back of our class was, “So wait, is your home worth $11,000 more with a Caucasian owner?” While I again assert that this experiment is done on a small scale and is not conclusive, and there are multiple factors in deciding why there is such a difference in value, the answer to his question remains the same: not necessarily, but possibly.

Photo credits:

The first picture was taken by Alana Balgnasay , the second was taken by Connor Poirier, and the last was taken by Brenna Lundhagen.