This post is by Grace Belfiore, who is Lead Researcher, along with Dave Lash of Dave Lash & Co, for NGLC’s MyWays framework. She is Principal Consultant at Belfiore Education Consulting. Follow her on Twitter @GraceBelfiore.

These days shout-outs to Project-Based Learning (PBL) and other forms of experiential learning are coming from all corners of the education world--take the showcasing of High Tech High in Ted Dintersmith’s documentary Most Likely to Succeed, the new It’s a Project-Based World campaign from Getting Smart and the Buck Institute (BIE), the announcement that New Hampshire will pair its focus on performance assessment with PBL professional development from BIE--and, closer to home, NGLC’s recent, lively Twitter chat on PBL.

Why We Are Cheering

NGLC is cheering this intensified interest for a very particular reason. For the past eighteen months our MyWays project has been researching the changing context for learner success in an increasingly complex and fast-changing world, and developing a framework to address the following three questions for school designers:

- How well are we defining and articulating what success looks like for students attending our school?

- How well does our design for learning and the organization of our school directly support students’ attainment of that richer, deeper definition of success?

- How do we gauge students’ progress in developing those competencies? And: How can we measure and articulate our school’s overall performance in helping all of our students achieve our definition of success in full?

For schools reflecting the principles of next generation learning, developing and activating strong, clear answers to this through-line of questions is imperative. But for some of these next gen innovators, and especially for the early adopter districts that are following them, we are finding that a vigorous nod to a broader, deeper success definition (see the MyWays expanded competency framework below) is too often followed by a quick jump to the third question of how to assess those competencies--but insufficient engagement with the second question: just what kind of learning design is needed to enable development of the broader definition of success.

The 20 MyWays competencies are grouped in four arenas:

Content Knowledge - subject area knowledge and organizing concepts essential for academic and real-life applications

Creative Know How - skills and abilities to analyze complex problems and construct solutions in real-life situations

Habits of Success - behaviors and practices that enable students to own their learning and cultivate personal effectiveness

Wayfinding Abilities - knowledge and capacity to successfully navigate college, career, and life opportunities and choices

What’s Needed in a Rich, Deep Learning Design

The MyWays model, in addition to synthesizing leading education, youth development, and school-to-work competency models, was also influenced by the environmental factors defining the economic and social world into which today’s learners are emerging. This new environment combines these forces:

- A deepening employment crisis for under-30s and a rapidly changing jobs landscape

- An increasingly fragmented and risky postsecondary education landscape

- A widening opportunity gap between lower- and higher-income students.

Every one of these forces increases the need for a broader, deeper set of competencies for all learners, and significantly shapes the kind of learning necessary to develop them.

In particular, a substantial majority of the competencies identified in the MyWays model require an integrated combination of thinking skills and real world abilities. Not surprisingly, especially in the arenas of Creative Know How, Habits of Success, and Wayfinding Abilities, “textbook learning” is insufficient. And brain science has shown that Content Knowledge and Creative Know How are also learned more durably and transferably in more integrated and authentic ways--the kinds of experiences that happen as part of well-designed PBL.

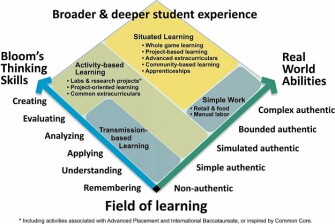

MyWays displays this interplay between thinking skills and real world abilities in its “field of learning":

Notice the golden rectangle of Situated Learning, which includes PBL along with community-based education, apprenticeships, and other authentic learning modalities. In this sweet spot, higher-order thinking skills are engaged within real world settings that are either bounded (within a controlled setting, or with some variables held constant) or complex (unbounded). This is learning that is embedded in activity, context, and culture, where social interaction and collaboration are essential, and novices learn from those more expert until they eventually become expert themselves--all key ingredients for developing the competencies needed by students today.

When it came to developing tools and guidance for educators to develop learning designs, the MyWays team was drawn to David Perkins’s Making Learning Whole framework because it highlights and integrates the elements that are particularly critical to the development of the broader and deeper outcomes that MyWays embodies. Perhaps most importantly, Perkins’s central message of “playing the whole game” (see #1 in the center of the graphic below) is perfectly aligned with the essential role of learners as active players in holistic experiences that carry meaning and require commitment (i.e., involve the “whole game”).

The seven principles of whole-game learning

Why Well-Designed PBL Is a Leading Whole-Game Learning Approach

This brings us back to PBL, which is perhaps the best known of the whole-game, situated learning approaches. (And while next gen educators have a lot to learn from a range of authentic learning approaches, including service-learning, place-based education, and well-structured apprenticeships, mining the current interest in PBL is an excellent place to start.) For some educators, seeing High Tech High students grow through their engagement in a hands-on, holistic “whole game” project in Most Likely to Succeed was just what they needed to open their eyes to the power and possibility of project-based learning (PBL).

But Hard to Do Well

At the same time, as Tom Vander Ark noted earlier this year with masterful understatement, “It’s easy to do project-based learning, it’s just hard to do it well.” What longtime practitioners of PBL know is that such authentic learning experiences contain a paradox.

In Part 2 of this blog, we will look at that paradox. It helps to explain why some educators who are totally on board with the expanded outcomes in MyWays’ Question 1 and even play around with the third question about assessment for these arenas, either underestimate or are scared away by what’s involved in Question 2--ensuring a sufficiently authentic, genuinely rigorous, and holistic learning approach.

I won’t give away the paradox here, but will reveal that one answer to it is this: sometimes you just need to see this kind of learning in action--when it’s done well--to experience as three-dimensional a version of experiential learning as possible.