This post is by Katie Rein, Instructional Guide at Arbor Vitae-Woodruff School in Arbor Vitae, Wisconsin.

In February of 2016 nearly 600 students and staff filled the gymnasium at Arbor Vitae-Woodruff School. We were seated on the floor in a semi-circle, listening intently as representatives from each grade level took their turn at the microphone to share their experience helping to collaboratively create a work of art that now graces our school lobby. Arbor Vitae-Woodruff Elementary School (AV-W School) is a credentialed and mentor school in the EL Education network, noted for its achievement across the dimensions of academic mastery and student character. This moment marked a big step forward in our progress on EL Education’s third dimension of achievement: high quality work.

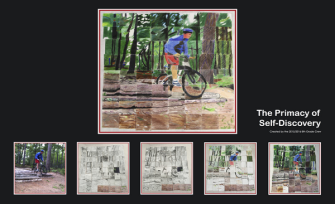

Each grade level had selected a photograph from a fall fieldwork adventure that connected to one of the design principles that articulate the values of schools in the EL Education network. The photograph was enlarged and cut into many pieces. Each student worked on reproducing one piece of the photograph.

Through the process, students learned to look closely at a high-quality model. They drafted, gave and received critique from their peers and teachers, collaborated to determine next steps, sometimes started over or radically revised, and finally produced a final product that surpassed what they thought was possible: a high-quality likeness of the original photograph that they had created together. Here’s what students had to say about the process:

- “I really didn’t think it would turn out this good in the end.”

- “It took courage to hear other people tell you what you didn’t do well, but [the feedback] wasn’t bad because they were kind and helpful.”

- “The biggest surprise for me was how much we improved from draft to draft.”

These sentiments were met with nods of agreement from fellow students who had grappled together on an especially challenging project. You can see the models each grade level used, as well as their drafts and final products in this video. Teachers responded to students’ comments with joyful and knowing smiles because before they led their students through this project, they too had experienced first-hand the work and the rewards of creating truly high-quality work. And stepping into the shoes of their students had made all the difference.

Developing a Shared Vision

Just a few months earlier, our staff did not share a vocabulary for describing the attributes of quality work, and we had few common instructional procedures for getting our students to produce it. Staff and students frequently used the word “craftsmanship,” because it was identified as a habit of scholarship we work on in our school. But people used the word craftsmanship differently, often simply to set a vague bar for high expectations when giving an assignment. Many teachers didn’t clearly communicate to students how to represent craftsmanship in their work. Students were expected to do so independently, and some students really struggled to meet teachers’ expectations of quality.

To “norm” our understanding of what high quality work is, and how to produce it, the staff used a protocol to look at student work and analyze it for complexity, craftsmanship, and authenticity. When we compared products across discipline and grade levels, we could see that while some students could produce work of high quality, many ended up creating mediocre products. They lacked purpose, knowledge of the intended learning, or how to make their work complex. Together, we identified specific practices that would support all students to create high-quality work.

The Power of Being a Student Again

While we now had a better understanding of what we were aiming for and the pedagogical steps to produce high-quality work, we still didn’t know what it felt like to be the student who “can’t draw” or the kid who takes critiquing a little too hard. And we weren’t practiced in giving each other critiques are is kind, helpful, and specific. To overcome these emotional hurdles to producing high-quality work, we used a series of staff meetings to participate in the very art project we would later do with our students.

Each teacher received a piece of a photograph, the model that would be analyzed to determine indicators of quality. As a group, we discussed what we would need to focus on to create a high-quality replica. We started our drafts, even though many of us felt uncomfortable doing art. Many were also anxious about sharing their work and being critiqued. To relieve their concerns, we used a fishbowl protocol to model how to participate in peer critique and set norms for giving and receiving feedback that is constructive and kind. This is exactly the progression that students would later use with their students.

As the process continued, teachers tackled multiple drafts with revisions focused on the elements of quality in the original model. Some teachers felt frustrated because the process was taking too long, even as they recognized that students feel the same way when asked to go back to the same work multiple times. Other teachers were determined to stick with it. They were driven to get it just right, and to persevere to the final product. In the end, teachers discovered they were energized to push students in the same way. They were truly proud of what they had accomplished individually and together in the collaborative whole and now knew both intellectually and emotionally how to support their students in getting to the same quality.

Shared Understanding and Commitment Leads to Deeper Learning

The progression of teacher and student collaborative art projects changed the culture at our school. When faculty and students have a shared understanding of and procedure for creating quality work, students know that they are developing skills that matter, ones they can apply in their future lives. Outside of school, individuals are judged not by how many questions they got right on a test, but for the quality of their work. Our students are now not only “OK” with receiving feedback from peers, they actually ask for it. They want to do multiple drafts. They collaboratively create rubrics to guide their work. Moreover, our teaching and learning practices around quality work have spread across the disciplines, so teachers are now using them for research, writing, info-graphics, and other kinds of products, as well as art. As a result, students create work that has a purpose and the power to influence an audience. You can see more of their products here.

Today, almost two years after the creation of the design principle posters, students can still be seen standing in front of the posters pointing to “their square,” the piece they drafted and revised, received feedback on, got frustrated with, and then determined to improve. This kind of pride shines a light on the hard work and excellence that come from learning deeply. It also reflects the sense of community that results from teachers and students doing the work of learning side by side.

Photo Credits: Arbor Vitae-Woodruff Elementary School