Note: Sarah Reckhow, assistant professor of political science at Michigan State University, is guest posting this week.

Thank you to Rick, for the opportunity to guest blog.

An education reform “movement” is underway. There is a common understanding of the who (Michelle Rhee, Joel Klein, Wendy Kopp, Bill Gates, Eli Broad, Geoffrey Canada, Reed Hastings, Jon Schnur, Steve Barr, Joanne Weiss, Jim Shelton) and what (charter schools, merit pay, Common Core, school choice, alternative certification, mayoral control) of this movement. But how have these individuals and ideas come together?

Private wealth has been an essential resource for supporting many of these leaders and their initiatives. Major foundations, such as the Gates Foundation, Broad Foundation, and Walton Family Foundation have financed the development of charter schools, advocacy organizations, education consulting and research organizations, and countless nonprofits. There is more to this story than individual grants to individual organizations. Education philanthropy has changed in the last decade, and changes in philanthropy have contributed to building the education reform movement. My research on education philanthropy points to three key changes (based on an analysis of grants from the top 15 K-12 grant-makers). Individually, these changes may not surprise any RHSU readers, but their combined impact is significant.

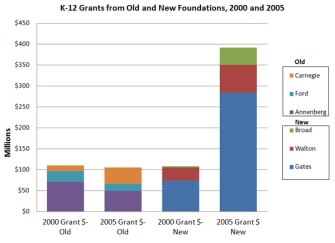

1. Dominance: The scale of giving from the newly dominant philanthropists (particularly Gates; Walton and Broad to a lesser extent) grew very quickly, and it far surpasses the giving of the “old guard” in education philanthropy (Ford, Carnegie, Annenberg). The accompanying graph illustrates this trend with data from 2000 and 2005. By 2005, new foundation grant-making was nearly quadruple the levels of the old.

2. Investing in the competition: Since 2000, major foundation grant-making has shifted away from public schools and towards sectors that compete with traditional public schools, such as charter schools. In 2000, grants for public schools (including school districts and state departments of education) composed nearly 40 percent of grant dollars from the top funders. In 2005, it was less than a quarter. Grant dollars for alternatives to traditional public schools, including charter schools and charter management organizations, as well as private schools, grew from less than 10 percent of grant dollars in 2000 to nearly 25 percent in 2005. Based on 2009 grant data, gathered by Patrick Carr for his dissertation at Georgetown, these trends have continued. The share of funds for public schools continued to shrink, while charter schools received an even larger piece of the grant pie.

3. Convergence: Foundation grant-making is increasingly converging--major funders are giving grants to the same organizations, and in some cases, the same school districts. The share of convergent grant dollars (the same organizations receiving grants from multiple major funders) grew from 21 percent in 2000 to 35 percent in 2005. Historically, foundations were known for funding their own pet projects, and overlap was less common. On top of the philanthropic convergence, a newer trend is the increasing overlap between foundation grant-making and federal grant-making (a subject of much discussion during the initial round of Race to the Top).

This new approach to philanthropy is often known as “venture philanthropy"--a term that links nonprofit grant-making to venture capital investing. This approach emphasizes “social return on investment"--making grants/investments that maximize outcomes. I see venture philanthropy as a label that is more aspirational than operational (and I suspect many philanthropists do as well). Even the most venture-oriented among the major education funders are not publishing social return on investment figures in their annual reports.

I call major education funders and their grantees the Boardroom Progressives.

Boardroom: Many of these reformers are connected to the business world, including the technology sector and management consulting, or they emerged as leaders of new education nonprofit organizations. They are skeptical about the traditional management of public schools, and many of their proposed solutions rely on organizations and leaders from outside of government.

Progressives: These reformers are idealists, much like the original Progressive movement of the early 20th century. The movement is animated by a vision: all children must have an opportunity for an excellent education and achieving this goal is a social responsibility requiring government action. The Boardroom aspects of the movement tend to appeal more to Republicans, while the Progressive elements resonate particularly with Democrats. This creates tension in the movement and makes the movement vulnerable to attack from both ends of the political spectrum. But it can enable cooperation with leaders from both political parties.

Boardroom Progressive foundations have revamped education philanthropy and built a new education reform organizational infrastructure. In my next post, “Let’s all grant together,” I will show how convergence has changed philanthropic and federal grant-making.

--Sarah Reckhow