Community schools in Baltimore received four of seven top honors from the Coalition for Community Schools, a Washington-based alliance of national, state, and local organizations that advocate for and help connect schools with resources for disadvantaged students.

The three other recipients of the National Community Schools Award for Excellence are in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake City.

Community schools are neighborhood hubs. They bring together a broad array of government, social services, and local youth and family development organizations to provide everything from academic and economic support to health care and enrichment activities for students and families living in some of the nation’s poorest neighborhoods.

“These schools are at the center of young people’s lives and their communities are there with them,” said Martin Blank, the director of the Coalition for Community Schools, in a written statement. “These winners represent the best of what can be done with teamwork and ingenuity in America’s communities.”

The Family League of Baltimore, which manages, coordinates and supports a network of 45 community schools in partnership with the Baltimore City Public Schools district and the mayor’s office, won along with three individual schools in the league’s system. They were credited with improving attendance, raising academic achievement, reducing the teen-age pregnancy rate, and increasing the number of students attending after-school enrichment and tutoring programs.

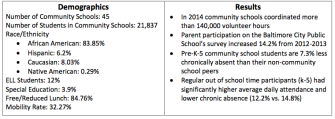

The 22,000 students enrolled in those schools live in the city’s most under-resourced neighborhoods, as shown below in the league’s chart. Many have no public libraries or recreation centers.

The league pays for each school to hire a community school coordinator responsible for assessing student and neighborhood needs and developing partnerships with the agencies that can provide those resources.

Benjamin Franklin High School vaulted from being one of the lowest-performing schools to one of the most sought after. Between 2011 and 2015, enrollment nearly doubled from 226 to 437 students.

Part of its transformation included $5 million in renovations funded by the school district, the state of Maryland, and the federal government. Local residents were involved in the redesign, which expanded the school to create a 3,000-square-foot community center that houses mental health services, a child-care program for children of teen mothers attending the school, and workforce development programs.

Dante de Tablan, Franklin’s community school coordinator said, in a news release, that when the school reopened after the reconstruction, some students called friends that had dropped out and urged them to come back.

At Baltimore’s Wolfe Street Academy, an elementary school serving a majority of English-learners, the reading proficiency rate for 5th grade students increased from 50 percent in 2006 to 95 percent in 2014, and moved from ranking 77th among elementary schools in the district to second place. And while most community and noncommunity schools had similar double-digit rates of chronic absenteeism—defined as missing more than 20 days of school—only 1 percent of Wolfe Street’s students missed that much school, according to a report by the Baltimore Education Research Consortium.

Students also receive three meals a day, free annual dental exams, and one-on-one tutoring from college students at Johns Hopkins and Notre Dame of Maryland Universities.

An extensive outreach program to local health and welfare agencies reduced both the teen pregnancy and infant mortality rates among families of students enrolled at the Historic Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Elementary School (HSCT), the third individual award winner in Baltimore.

The neighborhood where it’s located, known as Upton-Druid Heights, gained a measure of notoriety as the impoverished and drug-riddled community profiled in the television show, “The Wire”. More than 60 percent of the children live in poverty, nearly 40 percent of the adults never graduated from high school and the crime rate is one of the highest in the city.

Because of those conditions, HSCT is also one of four schools in the district within a U.S. Department of Education Promise Neighborhood, known as Promise Heights. Modeled after the Harlem Children’s Zone, promise neighborhoods are like community schools on a larger scale. HSCT and the three other schools in the Promise Heights initiative have agreements with the School of Social Work at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, to conduct home visits as a way of building trust and identifying needs. Their community school coordinators are all licensed social workers.

“I could fill HSCT with Ph.D.s to teach kids to read, but if I ignore the neighborhood, you still have the families and the traumas that they have,” said Rachel Donegan, the program director of Promise Heights, in a description of the initiative.

Having these networks in place also allows community schools to react quickly in emergencies, personal and public.

“When a family shows up on a Friday afternoon and says, ‘I’m going to be homeless tomorrow,’ they now have an immediate resource to refer that family both for emergency funding as well as 90 days of stability support, including mental health resources,” Julia Baez, senior director of initiatives for the Family League, told Education Week.

Baez said community schools were also some of the first to respond when protests erupted in Baltimore over the death of Freddie Gray, a Black man, while he was in police custody. Gray was arrested just blocks away from Upton-Druid Heights in a similar neighborhood.

“On the day that was happening our schools were making sure that kids had a safe place, our community schools became food hubs in neighborhoods all over west Baltimore because all of the grocery stores and corner stores had been shut down,” Baez said.

But, she added, the unrest also showed that there aren’t enough opportunities for many of Baltimore’s young people, and it will take a lot of money and collaborations to develop them. There are 183 public schools in the city; the Family League is only in 45 of them and can’t afford any more.

White House and Education Department officials will be on hand to present the awards when the winners are honored on June 10 at a ceremony in Washington.