(This is the last post in a two-part series on this topic. You can see Part One here.)

This week’s question is:

What are effective formative assessment techniques?

Part One in this series featured responses from Jennifer Serravallo, Andrew Miller, Daniel R. Venables, Brady E. Venables, and Larry Ainsworth.

Today’s post includes contributions from Libby Woodfin, Tony Frontier, Laura Cabrera and Alice Mercer.

Response From Libby Woodfin

Libby Woodfin, a former teacher and school counselor, is the Director of Publications at Expeditionary Learning and a co-author of Leaders of Their Own Learning: Transforming Schools through Student-Engaged Assessment and Transformational Literacy: Making the Common Core Shift with Work That Matters:

In our experience, what’s more important than any particular formative assessment technique is a commitment to involving and investing students in the process. Too often assessment is seen as something that is done to students, yet the root meaning of the word assess is to “sit beside.” Thinking of assessment as something teachers and students do together--metaphorically, and sometimes literally, “sitting beside” each other--changes the primary role of assessment from evaluating and ranking students to motivating them to learn.

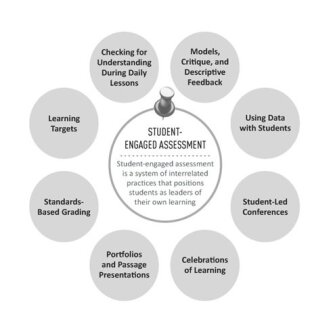

Our approach to assessment--student-engaged assessment--is a system of eight interrelated practices that positions students as leaders of their own learning:

Here we will highlight just a few: Learning Targets; Using Data with Students; and Models, Critique, and Descriptive Feedback.

Learning Targets Give Students a Goal to Work Toward

Rather than the teacher taking on all of the responsibility for meeting a lesson’s objectives, learning targets, written in student-friendly language and frequently reflected on, transfer ownership for meeting objectives from the teacher to the students.

The seemingly simple work of reframing objectives written for teachers (e.g., “Students will describe the differences between living and nonliving things”), to learning targets, written for--and owned by--students (e.g., “I can describe the differences between living and nonliving things”), turns assessment on its head. The student becomes the main actor in assessing and improving his or her learning.

Standards-based long-term learning targets can be broken down into daily lesson-level learning targets that help students stay focused on their learning goals every day while also giving them a picture of where they are headed over the course of weeks or months.

What’s most important is that students know what they are aiming for and are given multiple opportunities to assess their progress. You can view students at Odyssey School of Denver unpacking, using, and reflecting on the power of learning targets here.

Using Data with Students Builds Their Capacity to Reflect, Set Goals, and Document Growth

Teachers and school leaders everywhere collect and analyze data to make instructional decisions. However, in most schools the power of data to improve student achievement is not fully leveraged because students are left out of the process. When students learn to analyze data about their performance they become active agents in their own growth.

Providing students with the opportunity to identify their own strengths and weaknesses through data analysis gives them a powerful tool for learning. It moves conversations about progress from abstract, generic goals (e.g., try harder, study more) to student-determined, targeted goals (e.g., increase my reading level by 1.5 years, master 80 percent or more of my learning targets, ensure that 100% of my homework is completed and submitted) and provides them with skills to track those goals. In the data tracking form that follows, note the learning target at the top of the page and a clear system by which even a very young student can track her progress at periodic intervals.

When students learn to analyze data about their performance they develop a growth mindset [Based on the work of Carol Dweck (2006)]. They learn to see their intelligence as something that can be developed through hard work, not something that is fixed and unchangeable. Documenting their learning over time through data analysis helps them see the connection between their hard work and their achievement. You can see students at two schools in Rochester, New York, using data to reach their goals here.

Models, Critique, And Descriptive Feedback Are Tools for Improvement That Students Can Master

Standards do not create a picture of what students are aiming for--they are typically dry technical descriptions. When a Common Core literacy standard requires that students “use organization that is appropriate to the task and purpose” what does that mean? What does that look like? What if instead of always being disappointed in the writing our students turn in we worked together with them to examine exemplar models and unpack the criteria that make them high quality?

In the figure that follows we see the six drafts of a scientific drawing that first-grader Austin created. He and his classmates in Boise, Idaho, had looked together at models of butterfly illustrations and created the criteria and a rubric for strong illustrations. After each successive draft, Austin brought his illustration to his classmates who critiqued it against the rubric and gave him feedback. In the end, he was able to create a beautiful high-quality final product that resembled a scientifically accurate Tiger Swallowtail.

Models, critique, and descriptive feedback emphasize skills of critical analysis and self-assessment and ask students to make important decisions about their work and learning. Because the path to meeting learning targets is clearly defined by a shared vision of what quality looks like, students can work independently and build skills confidently.

You can view students learning about how Austin created his butterfly here.

Meaningfully engaging students in understanding their learning goals, tracking their progress, and, ultimately, communicating their learning to their families and communities is the secret sauce of assessment. School improvement can begin in many places, but in the end, it only succeeds when it is embraced and led by the hearts and minds of students themselves.

Response From Tony Frontier

Tony Frontier is an ASCD Faculty member and an assistant professor of leadership studies at Cardinal Stritch University. He is co-author of Five Levers to Improve Learning: Prioritizing for Powerful Results in Your School (ASCD, 2014) and Effective Supervision: Supporting the Art and Science of Teaching (ASCD, 2011):

Formative Assessment Strategy: Using Rubrics Formatively

The essence of formative assessment is that it is a process. I’ve seen too many teachers spend a weekend scoring student papers and providing copious amounts of feedback, only to have students glance at their grade or score and put their paper in a folder...never to be seen again. The goal in any system of learning is to develop the learner’s understanding of what quality looks like so the learner can judge and modify their own work. Rubrics can be a powerful formative tool in the formative assessment process.

To use rubrics in a manner that empowers students to see rubrics as a tool to guides the learning process rather than merely justify grades, three components need to be present.

First, teachers need to help students understand that rubrics can be used to guide efforts to produce quality work throughout the learning process. When students understand and can use words like clarity, synthesis, analysis, and interpret to guide their work, they are on a path toward quality. To these ends, words like synthesis and analysis - and other words that appear frequently on rubrics - need to be central to the process of curriculum, and instruction, and not just assessment.

Second, students need focused feedback throughout the learning process. Focused feedback provides the learner with specific information about the components of the product that are done well, areas that can be improved, and insights on how to improve. The amount of focused feedback depends on where the learner is in the learning process. The further the student is from the target, the less feedback he or she needs. Too much feedback can overwhelm, rather than empower, students.

Finally, students need to know that they are expected to respond to feedback in order to improve the quality of their work. When students are given shorter assignments or when larger assignments are scaffolded, teachers and peers can use rubrics to provide students with focused, timely feedback that can be used by that student to revise and clarify their work. Requiring students to respond to feedback through focused revision or having students use feedback to articulate goals for their next levels of learning empowers students as active agents in the learning process.

Response From Laura Cabrera

Laura Colosi (now Cabrera), an author and internationally recognized expert in parenting and education, holds a PhD from Cornell University where she taught for many years, and is co-Founder and senior faculty at Cabrera Research Labs in Ithaca, New York. She has more than fifteen years of research and teaching experience, also at Cornell University, where she taught coursework on Families and Social Policy and is the co-author of Thinking at Every Desk: Four Simple Skills to Transform Your Classroom (W. W. Norton; 2012). Visit her at cabreraresearch.org;

Formative assessment is a newer (1967) perspective on evaluation that contrasts to summative evaluation. Rather than focusing on outcomes and accountability, formative assessment is used to gather information to modify teaching practices before summative assessment occurs. In many ways, it gives a student (and teacher) an opportunity to correct thinking errors and see barriers to learning to increase student achievement on summative assessments, which are often tests and final grades. In the published literature on assessment, formative assessment has several purposes: 1) to modify instruction throughout the learning process as needed; 2) to get kids more engaged with their own learning; and 3) to develop student’s metacognitive awareness of how they build meaning through thinking about information.

No technique known to mankind is a better assessment tool than developing metacognitive awareness in students. That is, helping your students become more aware of the patterns of their thinking and how their thinking facilitates or impedes their own learning. They must understand what thinking is and how it happens in the human brain. Specifically, humans build knowledge by: 1) making distinctions; 2) organizing ideas into part-whole systems; 3) recognizing relationships among concepts; and 4) taking perspectives on any idea to better understand it.

We don’t want to do the work of forming young minds for them, we want to empower them to shape their own minds. In our classrooms, we use techniques and tools to help students talk about, draw, and build their thinking processes as an integral part of the learning process (and as an ongoing formative assessment). There are many tools and techniques for conducting formative assessment. They include: visual mapping of ideas so the teacher and student can check both the content and thinking skills a student used to understand a lesson; exploratory questions that spur thinking rather than push facts; and models and tactile manipulatives that allow a student to show his/her thinking about a topic. All of these tools highlight thinking errors or successes early in the learning process.

All of these formative techniques can be reinforced by a classroom environment that declares, “you are here to learn, think, build your own deep understanding, and work together; this is your classroom, your time, your life!” This constant metacognitive state is by definition a formative state of being. It means everything is under construction, not instruction, and we are all--both teachers and students--shaping learning every moment of every day. It transforms formative assessment from a technique to a disposition and a habit.

Response From Alice Mercer

Alice Mercer teaches sixth grade at an elementary school in Sacramento, CA. She started her career in Oakland, Ca, and moved to Sacramento in 2001. Alice is active in her union doing social media outreach, and is on State Council, the policy setting body of the California Teachers Association. Her blog is Reflections on Teaching:

My first thought on formative assessment is that it is not a final, but should give students, and teachers, interim feedback about where the student is at. This leads to the idea that they should also have the chance to act on that feedback and be either re-assessed, or have another chance to show they have mastered the content. It should not be a first and last chance to show knowledge and/or mastery.

What am I doing in my classroom? I’ve moved to a weekly short response assessment that has questions in the two content areas (science and social studies) and literature. I give students a choice of 2-6 questions to answer. I have students develop some ofthe questions when they do group discussion on what they have read.

Rather than a full-blown rubric, I have a check-list:

Does the response have a restatement of the question asked or make clear what they are answering?

Does it answer the question?

Does it provide supporting details?

Does it have good capitalization, usage, punctuation, and spelling?

I then translate this to a percentage grade for their overall writing, their knowledge of the subject matter, grammar, etc. Most importantly, students are given this feedback, and can revise their work to improve their grade. This is certainly not the only way to do this. I’m sure others will suggest things like checklist observations, etc.

Thanks to Libby, Tony, Laura and Alice for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org.When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo.

Anyone whose question is selected for weekly column can choose one free book from a number of education publishers.

Just a reminder -- you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email or RSS Reader... And,if you missed any of the highlights from the first three years of blog, you can see a categorized list below. You won’t see posts from school year in those compilations, but you can review those new ones by clicking on the monthly archives link on this blog’s sidebar:

Best Ways To Begin & End The School Year

Teaching English Language Learners

Teacher & Administrator Leadership

Education Week has published a collection of posts from blog -- along with new material -- in an ebook form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching.

Watch for the next “question-of-the-week” in a few days....