Jennifer Serravallo agreed to answer a few questions about her latest book, The Writing Strategies Book.

You might also be interested in the interview she did for this column two years ago, “The Reading Strategies Book": An Interview With Jennifer Serravallo.

Jennifer Serravallo (@jserravallo) is the author of over 10 books on reading assessment and instruction. She was a a NYC elementary teacher and later a senior staff developer at Columbia University’s Teachers College Reading and Writing Project. She has also taught graduate and undergraduate courses at Vassar College and Teachers College. Learn more or follow her blog.

LF: How do you define a writing “strategy.” How is it different from a “skill” or “technique"—or is it?

Jennifer Serravallo:

Writing strategies are how-tos to help a writer work toward a skill or a goal. For example, if a writer’s goal is to elaborate/add detail, a strategy that might help would be to think about the setting where the story takes place, think about your senses and describe the place with what you you’d see, hear, and feel in that place. Unlike a “technique,” writing strategies can do more than help improve the qualities of the writing or improve the craft. Strategies can also help a writer with habits and behaviors. For example, if a writer is trying to write with more stamina, without getting distracted, a strategy might be to think about what you plan to accomplish in the writing period, make a list of the specific things you want to get done, check them off as you work on them.

LF: You write in the book about the importance of writing “goals.” What does that look like—practically—in the classroom?

Jennifer Serravallo:

I think it’s really important that students have opportunities to self-reflect and decide what will help them improve most as writers. Once goals are established, students then know why we’re teaching the strategies we are—because the strategies are in support of a decided upon goal.

Goals can be anything from improving engagement, working on writing volume, trying to better organize their writing, considering the elaboration or details they include, or working on conventions (to name a few). Practically, I think it’s helpful for a teacher to share with the class that all writers have goals, and give them a list of possibilities and why a writer would choose a goal. Then, teachers can help students self-reflect by looking at their own writing. Once goals are determined for each student, teachers can give children a visible reminder of their goal, and teach strategies in conferences and small groups that support that goal.

LF: What are two or three writing strategies that you think might be particularly fruitful, but may be new to a majority of your readers?

Jennifer Serravallo:

It’s so hard to pick just a few! Also, the truth is that a strategy that may be most fruitful for one student might not be the best for a different student - it’s so important that we are teaching strategies not as activities, but rather in response to a student’s goal, which is ideally based on our formative assessment of their work. With that disclaimer, I’ll share a few that may be for writing goals that are less familiar.

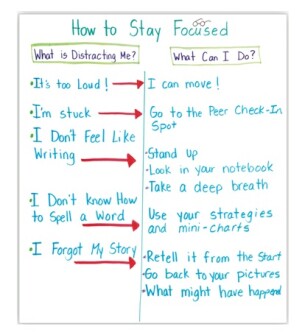

The first area is engagement. I think it’s important that we admit to kids that sometimes writing is hard, and as writers we need ways to block out distractions, keep our pencil moving or fingers on the keyboard, and silence voices in our mind that might be telling us “that’s not good enough” which can cause stall-outs. For example, one thing I like to brainstorm with a class of writers is a list of possible obstacles (I can’t concentrate, I’m stuck, I don’t feel like writing, I don’t know how to spell a word, I forgot what I was planning to do today...) and teach them that writers are problem-solvers. As a class, we can then create a list of solutions to the problems (move your seat, as your partner for a quick conference, check the word wall, re-read your writing). I realize I’m cheating a little here because that could really be a collection of strategies!

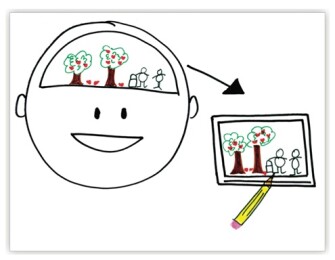

The second area is composing with pictures. I’m thinking now about our youngest writers in pre-K and K. Sometimes teachers wait to teach “writing” until children know letters and sounds, can record words on the page, know some high frequency words that they can spell automatically. Instead of waiting, we can teach children strategies for getting their thoughts and ideas down on the page by using pictures. Here’s one possible strategy with that goal in mind: Close your eyes and picture the story you’re writing. Name what you see. Open your eyes and draw what was in your mind. When you’ve drawn all you can, look back and ask yourself, “What was in my imagination that I don’t see in my drawing?” Add in any details that are missing.

LF: What are two or three strategies in the book that you think might provide a particularly “big bang for the buck”? In other words, ones where student outcomes have a good chance of being particularly positive but require less teacher prep and class time.

Jennifer Serravallo:

The strategies in the book cover different modes of writing—narrative, informational, persuasive, and poetry—and all steps of the writing process. So I’ll share two of my favorites from one mode: informational writing.

In the chapter about organizing writing, I have a strategy that I use myself as an author of informational writing. I find that I like to spend time in the beginning of the process, before drafting, to make sure I have a really clear “map” of where I’m going. I will often create multiple possible tables of contents to see which one best matches the focus for my piece.

For example, if I’m going to write about dogs, I could write a table of contents where each section is about a type of dog (dalmations, golden retrievers, yorkies, bloodhounds), or my table of contents could be organized by aspects of dogs (dog ears, dog fur, dog habits) or I could organize different ways to care for dogs (training your dog, feeding your dog, playing with your dog).

Each version of the TOC changes what it is I’m really trying to say, my focus for the piece, and also requires different detail from me to elaborate. So I like to teach kids to do the same - plan out many ways your piece could go, talk through each chapter with a partner to see where you have the details to fill the sections in, and use your preferred plan.

A second favorite strategy for informational writing is one that helps children use content-specific vocabulary. When children use good tier 3 vocabulary they will often assume their reader knows what it means. So I teach them that one of their jobs as a nonfiction writer is to teach their readers not only facts, but also words relating to their topic. The strategy goes like this: Look back through your draft for a place where you use an “expert word.” Then, add a partner sentence that either explains, defines, or compares so that you’re not just mentioning the word but also teaching your reader what it means.

For example, if I am writing about the moon and use the word crater, I could explain it by saying that if you look up at the moon in the night sky you will see dark spots. Those dark spots are craters. I can define it by saying that a crater is an indentation left in the surface of the moon from something that landed on it. I can compare it by saying that craters on the moon look like chocolate chips in a chocolate chip cookie.

In terms of prep work, I’d say that there are very few in the collection of 300 that require much preparation. I think the best preparation for writing teachers is to try the strategy out yourself, and to feel comfortable writing in front of students voicing over how you are using the strategy. Teachers are the primary writing mentor in the classroom, so the more students see their teachers write and use strategies, the better they’ll be able to try them out as they work independently.

LF: What are a couple of key pieces of advice you’d offer teachers who are grappling with how best to teach writing?

Jennifer Serravallo:

First, avoid the trap of giving students their topics and teach them strategies for coming up with their own topics. When you’re confronted with “I don’t know what to write about today!” avoid the temptation to give suggestions “You just went on a trip with your family to Disney! I’m sure you have a story from that trip that would be great to write about” and instead try to teach a strategy: Think of an important person, and memories with that person. Make a list of times you remember. Choose one and try to write the story.

Second, try to make sure you’re teaching students strategies they can use on their own, from piece to piece, rather than just fixing the writing on one piece. Again, this is so tempting - as the teacher, you’re a proficient writer and you know just how to spell that word, or where to put the punctuation so it sounds right, or what title would be a better title. But if you just fix the writing, you’ve done their work for them and the student hasn’t learned. The piece on the bulletin board will look better, but the learning isn’t there so you’ll need to do the same fixing on the next piece and the next and the next.

LF: Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you’d like to share?

Jennifer Serravallo:

I have to mention that this collection of strategies I’ve organized are not all my own invention. In many cases, the ideas are inspired by writers and teachers of writing I’ve looked up to for my whole career as a teacher and as an author. To name just a few of my sources: Nancie Atwell, Lucy Calkins, Ralph Fletcher, Katherine Bomer, Georgia Heard, EB White, Anne Lamott, Stephen King, Roy Peter Clark, Lester Laminack, Barry Lane, Noah Lukeman, Don Murray, Don Graves, Katie Wood Ray, Regie Routman, and William Zinsser. My hope is that readers of this book become inspired to seek out some of the original works of these greats in the field of writing and writing instruction.

LF: Thanks, Jennifer!