(This is the last post in a three-part series. You can see Part One here and Part Two here.)

The new question-of-the-week is:

How can you best differentiate instruction for English-language learners in a “mainstream” classroom?

Part One‘s responses came from Valentina Gonzalez, Jenny Vo, Tonya Ward Singer, Carol Ann Tomlinson, and Nélida Rubio. You can listen to a 10-minute conversation I had with Valentina, Jenny and, Tonya on my BAM! Radio Show. You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

In Part Two, Sandra C. Figueroa, Becky Corr, Sydney Snyder, Adria Klein, Michael D. Toth, and Barbara Gottschalk shared their suggestions.

Today, Judie Haynes, Debbie Zacarian, Eugenia Mora-Flores, Melissa Jackson, Joyce Nutta, and Carine Strebel contribute their ideas.

Response From Judie Haynes & Debbie Zacarian

Judie Haynes is an ESL teacher with 35 years’ classroom-teaching and teacher-training experience. She is the author or co-author of eight books and is the co-founder and co-moderator of #ELLCHAT, a widely known Twitter chat for teachers of ELLs.

Debbie Zacarian brings three decades of combined experience as a district administrator, university faculty member, and educational service-agency leader. With expertise in responsive leadership, instructional practices, family-school partnerships, and educational policies, she’s authored many books and local and state policies and presents extensively.

Judie and Debbie are the co-authors of Teaching English Language Learners Across the Content Areas; The Essential Guide for Educating Beginning English Learners; and Teaching to Strengths: Supporting Students Living with Trauma, Violence and Chronic Stress (with Lourdes Alvarez-Ortiz):

When instruction is differentiated, English-learners can learn the same content as their English-fluent peers because we are addressing their language and content-learning needs. Here are some strategies for differentiating instruction in mainstream settings.

Connect content to students’ background knowledge.

ELLs have rich personal, social, cultural, and world experiences. Take time to learn about each ELL’s various interests and experiences and connect these with the subject matter being taught. For example, a science teacher finds that a unit of study on genetics comes alive by having students study organisms that are native to the areas of the globe that they are from.

Provide instruction that ELLs can comprehend.

It’s critical for ELLs to meaningfully understand the subject matter being taught. In U.S. public schools, every ELL is assessed to determine their particular stage of English-language development. Each state provides descriptions of these stages. Learn about the stages of each of the ELLs with whom you work and design instruction and activities based on these. All ELLs benefit from bilingual bicultural instruction, particularly those at the beginning stages. When this isn’t available, find ways to provide meaningful translations (e.g., a peer, parent-community volunteer, Google Translate). Provide all ELLs with visual representations to introduce new concepts and vocabulary including graphs, organizers, maps, photographs, drawings, and charts. Create story maps and graphic organizers to teach ELLs how to organize information. Work toward depth, not breadth of information by eliminating all peripheral, nonessential information.

Use cooperative learning strategies.

We might feel compelled to use a lecture style of teaching (to be sure that we are covering the curriculum and more). However, paired and small-group learning experiences provide opportunities for students to interact and practice communicating in the subject matter they are studying and has been found to be a much more effective model of instruction than lecturing and remedy for the status issues that occur in our classrooms. ELLs and all students can benefit from participating in pair and small-group experiences when we assign them to work with peers who are likely to embrace them; model the tasks we want them to do; give them real reasons and meaningful tasks to use academic language; assign them roles (e.g., illustrator, timer, etc.) that they can understand and enact; and, when we continually observe students’ interactions and make adjustments to ensure that they can and are participating actively.

Identify key vocabulary and provide direct vocabulary instruction

Direct and explicit vocabulary instruction of key subject-matter concepts is essential for students to understand what they are reading and learning. The credo ‘less is more’ is important so ELLs aren’t overwhelmed. Select vocabulary that is absolutely essential. Explain the cognates, prefixes, suffixes, and root words of these. Carefully review vocabulary-concept words—phrases that have multiple meanings, such as ‘the three states of ‘matter’. Introduce the meanings of how it is used in a typical context and then in the context of the subject matter. Use photographs and drawings to teach the meaning of new words. Have students create visuals of the meaning of key vocabulary in the context of the subject matter used and display these on classroom walls and table mats. Provide ELLs with many opportunities to practice using key vocabulary in context.

Response From Eugenia Mora-Flores

Eugenia Mora-Flores is a professor in the Rossier School of Education at the University of Southern California. She teaches courses on first- and second-language acquisition, Latino culture, and in literacy development for elementary and secondary students. Her research interests include studies on effective practices in developing the language and literacy skills of English-learners in grades P-12. She has written nine books in the area of literacy and academic-language development (ALD) for English-learners. Eugenia further works as a consultant for a variety of elementary, middle, and high schools across the country in the areas of English-language development (ELD), ALD, and writing instruction:

Meeting the needs of your English-language learners is challenging for both the students and the teacher. Learning language alone is difficult; that coupled with learning content throughout the school day makes learning even more challenging. Teachers work hard to find ways to make this process manageable and successful for English-learners.

When working in mainstream classrooms, where the language needs of students are so diverse, the best place to start is by getting to know your students. Give them opportunities to use language throughout the day in order to assess their language development abilities and needs. Next, look for the language in your lessons. What are the academic-language demands of the lesson at hand? What language functions, forms, and vocabulary will they need to successfully learn and demonstrate learning in the lesson. Look for opportunities to bring language to life. How can we make language visible? And finally, offer multiple opportunities to practice using language with guidance and support (from you, peers, and tools). Thinking about the language demands of your discipline coupled with what you know about your students will guide your differentiation.

A few things to consider when supporting a range of language-learners in the classroom:

1. Getting to know your students: Offer a range of media to learn about and from your students.

a. Verbal exchanges offer opportunities to listen to your students’ language (content and fluency).

b. Written language opportunities (look for development of ideas, syntax, and clarity).

c. Hands-on opportunities (look and listen and watch for the development of ideas and knowledge).

2. Identifying the language of your lesson. Think about the core language functions students will need to access and share what they have learned. Will they compare and contrast, provide an opinion, defend an argument? Use this to provide sentence frames (forms) to guide students’ language output.

a. Provide a range of possible sentence frames to accommodate the different language levels in your classroom. For example, if we are comparing and contrasting, you might provide the following variety,

...and...both.

...and...are similar...

Where...can/has..., ....differs by...

Or provide cue words only for more advanced language learners (similar, different from, whereas, however, contrast).

b. Provide core vocabulary for the content at hand (use visuals or images as cues when possible).

c. Model language and point out where in the room they can access language supports. Students don’t always use the room as a tool for learning unless we make the use of the charts and posters explicit.

3. Make learning visible

Use media, visuals, graphic organizers, and other learning tools to guide student learning.

a. When providing directions or guidelines for learning activities or task, demonstrate with tools and explicit language. Show (not just tell) students what and how you expect them to complete the task at hand.

4. Providing opportunities to practice using language

Mix partnerships often so students have access to different language models.

a. Offer a variety of practices opportunities, oral and written. Students need to use language as much as possible to develop it.

Being intentional about language and allowing students to use language for multiple academic purposes will set the foundations for differentiation in mainstream classrooms to maximize learning for all students!

Response From Melissa Jackson

Melissa Jackson is an ESL teacher at Southeast Middle School in Kernersville, N.C., grades 6-8. Her husband is a high school assistant principal, and they have two high school teenagers. She loves film, voiceovers, and hanging out with her family:

I teamed up with one of our Spanish teachers, who is a native-Spanish speaker, for a professional-development workshop with teachers in our school. We began with the Spanish teacher giving them instructions in Spanish as I passed out a three-page story, written in Spanish, to each teacher. She did not use gestures, did not slow her speech, nor did she read it aloud. After a few minutes, one teacher raised his hand and asked if they could work together. We did not answer.

After another few minutes, we asked the group, “What could we do to help make this more comprehensible?” A few said it was hard to understand what was said in Spanish so maybe if directions were written on the board, it would give them time to process it since some words in English and Spanish were similar or they could look it up if they had a bilingual dictionary. Someone else suggested something visual that could help them to at least have an idea of what the story was about; to see if they had any (background) knowledge about the story. There was another suggestion about highlighting the important (key) words they needed to focus on. We overheard some teachers trying to partner with others who knew some Spanish. We asked if that would help them, and they all said yes.

All of these are a few things teachers of ELLs can do to differentiate instruction in order for it to be more comprehensible, AND they will help other students in the class, as well. Presenting it this way was an attempt to let teachers see what it may be like for ELLs in their classrooms. Other things that can help differentiate instruction is to use gestures, repetitive language, having a wait time for students to respond, and providing sentence frames for students to use to practice using English. CAN DO DESCRIPTORS are a great way to help teachers as well. This tool shows what each student Can Do based on their English-proficiency level in Listening, Speaking, Reading and Writing. This is a great tool to use for planning instruction, and each matrix has suggestions for each level. All of these things are some of the things needed for ELLs, and they will also help all students.

Response From Joyce Nutta & Carine Strebel

Joyce Nutta is a professor of English for speakers of other languages (ESOL) education at the University of Central Florida. She works with universities and school districts to integrate English-learner issues into teacher preparation and professional learning.

Carine Strebel is an assistant professor and ESOL coordinator at Stetson University. She teaches ESOL-focused courses, conducts training on instructing English-learners for her colleagues, and provides in-service professional development for school districts in the central Florida area.

Check out their book, Show, Tell, Build: Twenty Key Instructional Tools and Techniques for Educating English Learners:

Differentiating Academic-Subject Instruction for English-Learners

Part 1: Understanding the Classroom-Communication Gap

When considering differentiated instruction for English-learners, it’s important to recognize that they are not a singular group. One key distinction is an ELL student’s level of English proficiency, which develops over time. After arriving in English-medium schools, ELL students move along a continuum of increasing competency in listening, speaking, reading, and writing in English until they no longer are identified as English-learners.

Understanding the Student

To effectively teach academic subjects to English-learners, we suggest categorizing this continuum of English-proficiency development into three levels: beginning, intermediate, and advanced. These three levels are quite different from one another, and they divide English proficiency in a way that makes differentiated instruction feasible in a mainstream classroom. Standards for English Language Development, such as WIDA (see WIDA.us), divide English proficiency into five or six levels, so we recommend that these levels be clustered, with 1-2 as beginning, 3-4 intermediate, and 5-6 advanced.

According to WIDA, a student can say or write at level 1, “words, phrases, or chunks of language;" at level 3, “short and some expanded sentences with emerging complexity;" and at level 5, “multiple, complex sentences.” This developing ability to express oneself in English can interfere with comprehending, and showing comprehension of, new information that the ELL has been taught alongside non-ELLs in a mainstream classroom, especially for beginning and intermediate ELLs.

It’s clear that beginning, intermediate, and advanced ELLs need different types and amounts of support to achieve a lesson’s objectives. Those who can only express words or chunks (level 1) will have difficulty, for example, participating in a group debate about World War II, and those who express themselves in short sentences (level 3) will struggle to write a five-paragraph essay about political systems. Advanced ELLs may be able to use complex sentences, but they can be tripped up by unexpected problems such as idioms. For example, a level 5 ELL student we know missed the point of a reading passage because she thought the term “second nature” meant something unnatural and difficult since she reasoned that first nature would be natural and easy.

Understanding Language Demands of Classroom Tasks

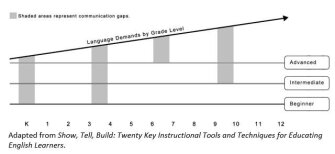

In addition to English-proficiency levels, teachers should consider the language demands of their lesson. As shown in the following diagram, classroom language demands rise with grade levels. When we look at rising language demands in comparison to English-proficiency levels, which can range from beginning to advanced in any grade, a gap emerges. This is not an achievement gap but rather a communication gap caused by the divide between the ELL student’s English proficiency and the language demands of the grade. The lower the ELL’s proficiency level and the higher the language demands, the larger the gap between the student’s current level and the language used and expected in the classroom. A beginning kindergartner has a smaller gap than a beginning 4th grader, but an intermediate 10th grader has a larger gap than a beginning kindergartner.

Most teachers are not fully aware of how the language they use, and the language they expect their students to use, can be a barrier for ELLs. To help them see where English -earners may need support, we developed an acronym, TREAD, that reminds them that anytime the teacher or students are Telling, Reading, Explaining, Asking/Answering, or Discussing, they are placing language demands on their ELLs. Whenever there is TREAD in a lesson or activity, ELLs may need support. The amount and type of support differs by the extent of the gap between their current proficiency level and the language demands of the lesson or activity (TREAD). In Part 2 of this article, we will share tools and techniques for providing this needed support.

Differentiating Academic-Subject Instruction for English-Learners

Part 2: Providing Communication Support

n Part 1 of this article, we discussed the communication gap that occurs between English-learners’ level of English proficiency and the language demands of classroom tasks (e.g., listening to the presentation of new information, participating in a small-group discussion, solving a word problem, etc.). Phase I of our Instructional Differentiation Decision Map, presented below, helps determine the size of the gap. The Task icon in Phase I depicts this first step in planning differentiated instruction for ELLs—analyzing the language demands, or TREAD, of a classroom task. The adjacent Student icon illustrates three levels of proficiency we suggest academic-subject teachers should differentiate for. Whenever the language demands of a learning task exceed the English proficiency of an ELL, teachers should provide communication support to narrow the gap (Phase II). Phase II helps teachers determine which supports are most helpful for each student (Step 1), and how (Step 2), when, and by whom (Step 3) they should be used or led.

Phase II: Narrowing the Gap Between the Task and Student

As seen in Step 1, we categorize communication support for academic-subject instruction as mainly verbal (through language, such as a glossary) or mainly nonverbal (through means other than language, such as graphics). There are many different verbal and nonverbal tools and techniques that teachers use to provide support for ELLs. An example of a nonverbal tool is the use of physical objects, such as a mechanical model of the solar system, which shows the elements of the system as well as how they move in relation to one another. If this information were presented primarily by description (and perhaps a photo), English-learners would have to depend more on language to acquire the content knowledge. By using a model and naming and indicating its parts and movements, teachers not only help ELLs learn the content but also the associated academic language. Nonverbal support for ELLs is generally helpful for non-ELLs, too, and can be used for the entire class.

The other type of support, verbal support, is much more dependent on the ELL’s Englishproficiency level. We group instructional tools and techniques for verbal support into those that moderate language demands according to the student’s English-proficiency level, such as providing a shortened, simplified reading passage, and those that temporarily elevate the ELL student’s language competence, such as word banks and sentence patterns for ELLs to use while speaking or writing. For a social studies reading and writing assignment, for example, an ELL at the beginning level would need the shortest, most simple reading passage, as well as sentences to complete with only one or two missing words, until her English proficiency rises. An intermediate ELL could read more complex text and write more complex sentences, supplying more of the language himself. Our website lists 10 communication-support tools and techniques that we think all teachers of ELLs should use and includes online resources for each. These tools and techniques can be used in combination to provide maximum support where necessary.

Once teachers choose their go-to tools and techniques for supporting English-learners’ comprehension and expression of academic subjects, they can plan to implement them by following Steps 2 and 3 of the Instructional Differentiation Decision Map. In Step 2, teachers determine whether extra support for their ELLs can be provided as part of support for all students, such as the solar system example. This planning step also considers whether the support can be a supplement that allows ELLs to do what other students are doing, as with a glossary to accompany a grade-level reading passage for an advanced ELL, or if the gap is so wide that the ELLs should work together by proficiency level, using an app that presents information graphically and with carefully selected language, for example.

Step 3 examines when support can be provided and who can provide it. For example, the nonverbal support of graphic organizers can be provided prior to a lesson, illustrating key vocabulary and points the ELL should focus on. Other times, support is best provided during the lesson (e.g., ready-made sentence frames for discussion activities) or after the lesson (e.g., ELLs draw concept maps to confirm comprehension). The timing also pertains to resources and collaborators available to classroom teachers, such as bilingual aides and technology-directed activities. A teacher can only be in one place at one time, but if she has collaborators, they can work individually with ELLs during whole-class and small-group instruction.

Schools follow different instructional and staffing models, so teachers should plan support for ELLs that is feasible and appropriate, given their school and classroom affordances. Using our Instructional Differentiation Decision Map reminds teachers of important considerations when planning differentiated instruction for ELLs.

Thanks to Judie, Debbie, Eugenia, Melissa, Joyce, and Carine for their contributions.

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo.

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching.

Just a reminder—you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email or RSS Reader. And if you missed any of the highlights from the first seven years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. The list doesn’t include ones from this current year, but you can find those by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Best Ways to Begin The School Year

Best Ways to End The School Year

Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

Teaching English-Language Learners

Entering the Teaching Profession

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributers to this column.

Look for the next question-of-the-week in a few days.