(This is the first post in a two-part series)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What are the best ways to integrate writing in social studies classes?

In schools, all of us need to be writing teachers, incuding those of us who teach social studies. This series will explore specific ways to integrate writing in social studies classes.

In addition to the ideas discussed by contributors to this two-part series, you might also want to explore The Best Resources For Writing In Social Studies Classes, The Best Scaffolded Writing Frames For Students, and previous columns appearing here on Writing Instruction and on Teaching Social Studies.

Today, Stan Pesick, Ben Alvord, Dawn Mitchell, Rachel Johnson, and Rebecca Testa-Ryan share their suggestions. You can listen to a 10-minute conversation I had with Stan, Ben, Dawn, and Rachel on my BAM! Radio Show. You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

Response From Stan Pesick

Stan Pesick currently works with both the Bay Area (California) and National Writing Projects and the Lesson Study Group at Mills College, Oakland, Calif. He taught American history and American government/economics in the Oakland Unified school district (OUSD) for 18 years (1976 - 1994). Between 2001 and 2013, he co-directed OUSD’s History/Social Studies Department and its programs focused on curriculum and professional development. Since 2014, he’s also worked as a curriculum consultant to the National Japanese American Historical Society and teh National Park Service:

Below are three ideas that can help students develop the skills and understandings necessary for writing, and have something meaningful to say, in history-social-studies classes.

I. History as Inquiry

If writing is actually thinking, it’s best integrated into history-social-studies classes when connected to specific ideas, events, and people at the center of what is being studied. For writing to be meaningful and engaging, it has to be about something and supported by teaching that unites the writing and the content. A first step in that process is developing good inquiry questions that frame lessons, units of instruction, and investigations.

What makes a good inquiry/argumentative writing prompt?

- Generates discussion and encourages varied points of view.

- Demands an answer that is not just a simple yes or no.

- Demands a critical or careful reading of the text(s).

- Moves beyond opinion, into positions that connect claim, evidence, and reasoning

II. Working With Models

In history-social-studies classrooms, students can be asked to write in a variety of ways, including narratives, explanations, interpretations, and evidence-based arguments but may not often get a chance to actually read the kinds of writing they are asked to produce. A common activity in history these days has students working with primary-source documents and brief background pieces, including a textbook excerpt, that provide some context on the time and place where the sources were created. But a source document is just a piece of the past to be analyzed and interpreted; it is not written history, and a brief background piece or a textbook excerpt is most often not a good example of well-written history.

Students need to read and discuss good examples of the kind of writing we are looking for; we need to make visible what we have in mind. For students to understand how to construct a historical account, they need the opportunity to discuss, analyze, and appreciate well-written history. Consider this historical narrative and interpretation the historian Nell Painter uses to begin her book, Exodusters (start with link to Page 3 and read through “no longer...” towards the bottom of Page 5). As you read, consider how the following questions might help students better understand what comprises quality historical writing.

- Who were the Exodusters, and why does Nell Painter write about them?

- How does the brief narrative about the Solomon family help you understand what’s happening in this place and time?

- What argument is Painter making about the hopes and dreams of African-Americans in post-Civil War America?

- What are the key pieces of evidence Painter uses to support her arguments around Reconstruction and the hopes and dreams of African-Americans?

- What questions do you have about the content of this piece? What more do you want to know?

III. Annotation: Writing that prepares for writing

Working with source documents, as part of work within an academic discipline such as history, economics, or geography, requires a specific kind of conversation between reader and text. In history, this conversation begins with “sourcing” questions, which ask the reader to read “around” the historical text, noting time, place, authorship, and other information about the text’s origins and historical context. It is then continued with a close examination and conversation with the text itself. What information, perspectives, ideas, and questions are communicated and raised?

Below is an example of what an “annotation guide” for working with historical sources might focus on in preparing a student to read and analyze an historical source. It can easily be adapted for the reading of source documents connected to other subjects and disciplines.

A Guide to Annotating in History

Identify, comment on, or question the words, ideas, and/or perspectives that:

- Provide information on who created the document, when, where, and for what audience;

- Illustrate how the creator of the document might have viewed the historical question, event, or individual at the center of your historical inquiry;

- Provide insight into what reasoning you will use to analyze the documents and develop your argument; i.e., criteria-based evaluation, cause and effect, cost-benefit, analogy

- You will use to support the argument you develop in response to the inquiry question;

- You disagree with and will need to counter as you develop your argument in response to the inquiry question.

- Intrigue, confuse, or trouble you?

Response From Ben Alvord

Benjamin D. Alvord is a 7th and 8th grade history teacher in Utah’s Tooele County school district and a Hope Street Group/NNSTOY Utah Teacher Fellow:

Moving from Students to Historians

Social studies is under attack in the education world. This is not a revelation to teachers of this subject, but as the required courses are whittled away in many states, we have to fight against this and against students who don’t share the same passion for history that we do. One way to do this is to turn your students into historians.

A great way to make students historians is to have them answer a historical question in your class. The Stanford History Education Group, or SHEG (sheg.stanford.edu), has created many lesson plans that have this premise. One of these is the “Battle of Lexington” lesson plan. Like many other things in history, there are open questions regarding this battle. This lesson centers around the question of “Which side shot first?”.

Asking students to provide an answer, in the correct way, to questions that remain unanswered makes them historians. Provide your students relevant primary sources that show multiple accounts of the same incident and allow them to find the answers on their own. Of course, to do this, you will have to provide them with some skills.

Utah and many other states are moving their standards from content-based standards to skills-based standards following the C3 Framework provided by the National Council for the Social Studies. Many of the skills listed in these frameworks are the skills you would use in a lesson plan such as the “Battle of Lexington” and other SHEG lesson plans. For this lesson, students will need to know sourcing, corroboration, and contextualization. SHEG also provides lesson plans to help teach your students these skills. Once the students have these skills, they can show them off by writing an essay.

Another benefit of a lesson like this is that it lends itself easily to another important task in education, which is integrating writing into your curriculum. The best way for the students to answer an open historical question is with an argumentative essay. The students are then forced to identify the results of their sourcing, corroboration, and contextualization. This can be done at any level. I often hear from my elementary school peers that they have little time to teach social studies in their classroom. A lesson like this allows you to teach social studies while teaching a language arts lesson. You can also scaffold lessons like this for younger students by rewriting primary sources into more accessible language while keeping the original intent. Students no matter what level love to argue.

Another issue we deals with as social studies teachers is apathy in our students. When you allow students to find answers on their own rather than giving them the answer, it allows them to have that moment of discovery that can engage them. Moments of discovery are what drew us in to being lovers of history, and it can be the same for our students.

As social studies teachers, we have to step up and defend our subject from the attack it is under. To do this, we have to be willing to adapt to a changing world and changing priorities in the world of education. Integrating skills-based lessons and writing into our curriculum is a great way to do that.

Response From Dawn Mitchell & Rachel Johnson

Rachel Johnson has taught social studies at the elementary and middle school level for the last 13 years. Currently, she teaches 7th grade social studies at Fairforest Middle School in Spartanburg District Six in Spartanburg, S.C. Rachel continually serves on several social studies committees for the S.C. education department and provides professional-development opportunities in social studies for teachers. Connect with Rachel on twitter @RachelJ62201984

Dawn Mitchell serves in instructional services in Spartanburg District 6, where she leads the induction and mentoring program as well as provides professional development in literacy and in project- based learning. Dawn is also an adjunct instructor at Furman University, where she currently serves as a university supervisor and teacher mentor. Connect with Dawn on twitter @dawnjmitchell:

Show What You Know: Using Principles of Visible Learning to Integrate Writing Into Social Studies

Effective teachers of social studies view writing as a natural and necessary tool for learning. When we integrate writing within the discipline of social studies, we are using it as a way for students to show what they are learning. Just as historians would, students are using disciplinary writing to build inquiry and knowledge of the given time frame and topic. This approach to writing isn’t an additional assignment. Instead, it is a pathway toward increased student interest, inquiry, and engagement not just in the activity or the product but also in the authentic process. Through using principles of visible learning, students become active learners in the social studies classroom, not merely passive paragraph writers or test-takers.

1.) Claim/Support/Question with Primary Source Analysis—One of the most engaging ways to build interest and background knowledge in social studies is to have students experience the topic from viewing primary sources from the time period. Rachel writes, “In my classroom, students analyze primary sources such as pictures, political cartoons, letters, maps, propaganda posters, just to name a few.” I have found when I have my students analyze primary sources at the beginning of a unit, they actually build a sincere interest in the topic of study that has been built from their primary-source inquiry and analysis. After the initial viewing, I have students write down their wonderings/findings. They write down what they notice, what the primary source prompts them to question/wonder, and what they infer the historical context is. One of our favorite primary-source analysis tools is from the American Library of Congress. Click here to view: Primary Source Analysis Tool.

Example (children playing among the ruins in East Berlin):

Photo Credit: Digital Public Library of America

2.) Connect/Extend/Challenge with Exit Slips—Formative assessments are a great way of knowing what your students learned and to gauge pacing for upcoming lessons. One digital exit slip tool is Connect/Extend/Challenge. Through this exit slip, students are able to connect learning from the recent lesson to previous learning. They are able to consider what they learned that extended/changed/or challenged their learning as well as any new questions they may have. Rachel writes, “Not all exit slips are this extensive. Many times I will use a backchannel like TodaysMeet or a padlet with open-ended questions specific to that day’s content that I want to find out students’ responses to in order to determine student understanding. For example, one that I have used often with United States history is “What is something that we talked about that you think will have an effect on future events in our country’s history?” Typically, my exit slips are targeted to a specific skill or concept that I want to make sure students grasp. Not only are their responses beneficial to me as their teacher, but the process of writing down their thoughts and reading the responses of their peers, allows for their further learning.

Example: Padlet Board

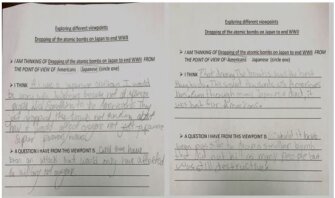

3.) Circle of Viewpoints with Perspectives—It is important when teaching history to students that they consider multiple perspectives, not just the most popular or common perspective. For example, if you are teaching a battle in American history, it is typical for the historical perspective to be written favorably toward the winner. However, effective teachers of social studies know that all historical accounts are biased and need to be evaluated to identify the inherent bias and strive to seek the complete story. Students need to understand all aspects of the event, and this requires them to recognize and value multiple perspectives. Rachel writes, “This approach to teaching social studies is cross-disciplinary as it applies to literacy with point of view, and I argue it is extremely valuable with present-day social interactions with their peers. Imagine how different our society would be if we all looked at every side of an argument before making a decision.” A recent example from my classroom was when we talked about the ending of WWII in the Pacific Front. It is very easy to see the dropping of the atomic bomb from the American point of view; however, I challenge students to think about this event from the Japanese perspective. We discuss the Japanese mentality of “Never surrender” as part of their culture, and surrendering to the Allied forces was not an option. To help students understand this event and the Japanese perspective, I chose a read-aloud. Shin’s Tricycle, which narrates the true account of a 3-year-old victim of the Hiroshima bombings. Students then visit the website of the Peace Museum to see actual photographs of Shin and his tricycle.”

Example:

Response From Rebecca Testa-Ryan

Dr. Rebecca Testa-Ryan is a Latina educator who has worked for the the Chicago public school district for 23 years. Rebecca received her doctorate degree from Loyola University in curriculum and instruction, a master’s degree in special education and administration, and a bachelor’s in history. She grew up in Humboldt Park and has taught in that district to model the importance of leading by example:

I have been a social studies teacher for 23 years and I have developed my teaching beyond presenting concepts of government, geography, history, economics, and current events. In my view, the teaching of social studies is an opportunity to integrate curriculum, such as writing, to augment the connection between the content presented and the student experience. Written communication is quite possibly the most significant form of expression; the skill to articulate through writing allows each student the freedom to share their analysis of historical events in a meaningful and effective way. As an educator, it is my responsibility to assist my students to develop those skills that will enable them to organize their thoughts, formulate arguments, and support ideas. Developing students’ writing skills should not be an isolated practice only experienced in a language arts class. In my case, I find various way to incorporate writing in social studies to prepare my students for the transition from middle school to high school, as well as beyond this, where acquiring written skills is critical.

The simplest way to have daily writing in my social studies class is to make available individual copies of primary sources to analyze. The purposeful grouping of students and the usage of appropriate academic language to analyze and evaluate sources initiate channels into meaningful accounts of the past. Students learn to listen and observe and value each other’s interpretation of sources. Once students have processed the sources visually and exchanged their ideas, it is then when students will demonstrate their individual experience in written form. Peer to peer interaction and discourse becomes part of the writing process as they engage with the same materials but have unique points of view.

As we begin the school year, I provide my students with framed paragraphs until they are more comfortable with the structure of an academic paragraph. Once they have developed an understanding of the structure, we go deeper and identify the paragraph’s purpose, why the paragraph is relevant, what evidence will be used to support their argument, how to show the reader that evidence adds to an argument, and how the conclusion shows the significance of the evidence a writer has presented. When I observe students are prepared to take on more, I challenge them by responding to three writing tasks a week. As students see a piece of work that they have successfully mastered, they feel a sense of confidence and are ready to take on the next challenge.

The last writing activity I would like to share is one my students enjoy completing. I call it “Wocabulary-Writing and Vocabulary.” Depending on the academic level of my students, I provide Tier 1, 2, or 3 vocabulary words from the historical period we are covering. I give my students the title of the writing assignment with the list of four, six, or 10 words placed in the center of the paper. My nonreaders can also participate by making a story board using illustrations of each vocabulary word and present to the class. Students who are given 10 words can divide the words to make two paragraphs if they wish, but they must make certain the historical account is accurate. They may use the vocabulary word in the beginning, middle, or at the end of a sentence. On many occasions, students have properly used three vocabulary words in one sentence. The goal of this activity is to force students to think critically, use academic vocabulary appropriately, enjoy writing, and have some fun during social studies class.

Thanks to Stan, Ben, Dawn, Rachel, and Rebecca for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo.

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching.

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email or RSS Reader. And if you missed any of the highlights from the first seven years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. The list doesn’t include ones from this current year, but you can find those by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Best Ways to Begin The School Year

Best Ways to End The School Year

Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

Teaching English-Language Learners

Entering the Teaching Profession

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributers to this column.

Look for Part Two in a few days.