(This post is the first in a four-part series)

The new question-of-the-week is:

What is agency and how can teachers encourage its growth among students?

“Student agency” is a term that is tossed around in education circles. This series will explore what it means and what it looks like—practically speaking—in the classroom.

Today’s contributors are Keisha Rembert, Sarah Ottow, Laurie Manville, Dr. Alva Lefevre, Dr. Lynell Powell, Dr. Felicia Darling, Paula Mellom, Rebecca Hixon, and Jodi Weber. You can listen to a 10-minute conversation I had with Laurie, Sarah, and Keisha on my BAM! Radio Show. You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

You might also be interested in The Best Resources On Student Agency & How To Encourage It.

Response From Keisha Rembert

Keisha Rembert is an 8th grade English and U.S. history teacher at Clifford Crone Middle School in Naperville, Ill. Keisha feeds her love of learning by continually refining her craft and has been the recipient of several grants affording her the opportunity to take courses at some of the world’s most renowned universities. She has recently been named Illinois’ History Teacher of the Year for 2019:

Student agency is ownership. It is command. An active process of engagement and authority over your learning. Teachers must deprivatize education for students to own it. Teachers must be coaches and facilitators and open the classroom floor up to the students. It can never be about covering a subject. I often ask my students questions and let them lead. They run groups and discussions. They tell me how we should assess ourselves. They tell me what is going good and bad in the classroom and how we can fix it. I started a feedback form I had been introduced to at a PD session. It was a biweekly form that gave students agency over content and more in the classroom. It is powerful. I do think I could and need to take that a step further and somehow turn it over completely to students.

Response From Sarah Ottow

Sarah Ottow is the founder and CEO of Confianza. In the U.S., Sarah has served as a classroom teacher to inner-city students, ESL teacher to marginalized neighborhood communities, instructional coach, district coordinator and mentor, and bilingual reading specialist, as well as ELL director for the Center for Collaborative Education in Boston. Internationally, Sarah has taught and consulted in private schools in Latin America, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe. She is also the author of The Language Lens for Content Classrooms: A Guide for K-12 Educators of English and Multilingual Learners:

Agency for students means moving from more traditional, teacher-centered ways of teaching to more innovative, student-centered ways of teaching. It means making sure that students get to make decisions about their learning, becoming actively engaged in the learning and assessment process. In a classroom that builds student agency, students know what they are learning, how they are learning, if they have learned it, and what to do with this learning.

To encourage agency among students, teachers can go beyond “covering” curriculum to engaging students in the process through connecting to students’ backgrounds on a topic, through evaluating their own learning styles, and even giving students ownership over what they are interested in within the given curriculum framework. A KWL (What do you Know, What do you Want to know, and What did you Learn) model can be a useful framework to work through to encourage student agency when teaching a unit. Start a unit by asking students what they know about the topic and generate a discussion about students’ experiences of this topic and what they are interested about learning. Post student ideas and the language they use or have students draw or write what they know to share. Then offer students an opportunity to predict what they will learn and share what they are interested in knowing. Spending time with students in a “What do you know?” and “What do you want to know?” can pay off in the long run because students can get hooked on the topic and generate their own knowledge versus just being receptacles of what knowledge the teacher dispenses. Throughout the unit, students can keep track of answering the question, “What did you learn?” as well as what skills and strategies they have been using to make progress.

I like to remember what Jim Cummins says, “No learner is a blank slate” and I always have tried my best to connect to something students bring to the classroom even if a topic is unfamiliar to them or it seems irrelevant to their lives. One way you can honor different levels of familiarity with a topic or a concept is having students rate their “level of knowing” with a scale: 0 = I’ve never heard of this; 1 = I think I’ve heard of this but I can’t tell you what it means; 2 = I’ve heard of this and I can explain what it means; 3 = I can teach someone else what this means. Furthermore, language-learners really need to practice language through discussions, reading, and writing, and what better way to do that than by having students consistently refer back to what they have learned to monitor their own growth. Beyond the KWL, teachers can use student-generated goals for language and/or for social skills throughout any lesson. Some examples of language goals that student generate themselves is explained in this article.

Response From Laurie Manville & Dr. Alva Lefevre

Laurie Manville is an ELD teacher and instructional coach at Brookhurst Junior High in the Anaheim Union High School district in California. She enjoys helping her students figure out what they are meant to do in life and guiding teachers in lesson-design creation. In her free time, you will find her backstage (or near a stage) assisting with line memorization, costumes or concessions, analyzing a screenplay, or at home journaling or mastering PiYo.

Dr. Alva Lefevre has been a language teacher, administrator, university professor, and teacher trainer for almost 40 years. She is passionate about working with English-learners and finding ways to apply educational research to the classroom. In her spare time, Alva enjoys traveling, gardening, and art.

Laurie blogs with Dr. Alva Lefevre at L&M Educational Consulting on their Facebook page and their new website, Educators in the Know:

Student agency boils down to students having a voice in the classroom, choices about how they learn, and how they show what they know. Most important is giving students a voice— meaning giving them the language and the opportunity to express their needs, as well as a mechanism to influence how the class is conducted. Classroom activities should be meaningful and relevant to learners, driven by their own interests, and, where possible, self-initiated with support from their teachers. To encourage agency, teachers need to build in options for learning and assessments and students must understand that they can demonstrate their understanding in more than one way.

One simple, but powerful mechanism that gives students voice in how class is conducted is the consistent use of the Exit Ticket. I am a techie teacher, so I have used Google forms, digital polls, and Kahoot as exit tickets. Here’s a Google Form that focuses on the lesson’s importance and relevance, as well as student readiness: Exit Ticket. (You might want to use this particular exit ticket after a more difficult concept has been presented.)

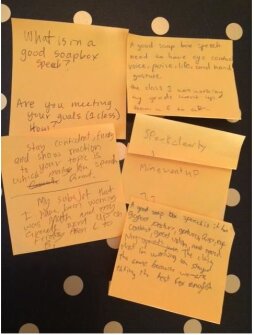

This year, I found that establishing a regular “sticky note” exit-ticket routine in my middle school class became a low tech but dynamic way to provide a platform for student voice.

How I make the sticky note work is by having students write a response to a question: personal, academic, organization-related, socio-emotional, community-building-oriented. (e.g., Were they OK in their other classes? How were things going with family and friends? Was their GPA something they could be proud of?) They record their thoughts, comments, or questions on a Post-it note and stick it onto a designated class space. Here’s one of my sticky-note questions and student responses:

Our space was located next to the classroom door and was entitled “What We Learned Today.” The space became much more than just “what we learned” so I’m thinking I’ll change the title next year to reflect student voice—maybe something like “Your Ideas are the Road to Change—#Inspired.” Sometimes student ideas drove the direction in a unit of study. For example, when the class and I discussed possible action civics projects, homelessness and school uniforms were the unanimous choices.

When I first started this routine with my students, I was surprised how completely engaged they were when we discussed the sticky-note contributions at the beginning of class the next day. I think the primary reason it was so engaging was that students truly felt heard. Sometimes I grouped like sticky notes together, showed the class, and commented on the answers. Sometimes I would address specific questions and feedback. I think that physically holding the student responses, reading from them, and grouping them added more significance to the contributions.

The Single Point Rubric is one of the more complex ways student voice and choice is integrated into my classes. The Single Point Rubric is a powerful tool and anchor for learning goals, feedback, and reflection. The tool has a place for criteria and for written feedback. It’s an excellent place to start when creating a space for teacher-student conferences. Reflecting on the feedback, referring back to a product—written, oral presentation—allows for a deeper type of student agency based on revision. Single Point Rubric created for an ELD 1 and 2 class combo creating ePortfolios. Single Point Rubric created with AUHSD ELD collaborative team with a focus on oral presentations for the Expanding (intermediate) proficiency level.

What makes the conferencing and revision a deeper kind of student agency is that students ultimately have a choice in whether or not they actually make any of the teacher’s suggested changes. Hopefully, the teacher’s guidance will help the student through questioning and through giving options to make a piece stronger or more refined. If a good teacher-student relationship is built, and students see the value in making whatever change is suggested, it is more likely that a student will make commitments to change and will follow through on those commitments.

Response From Dr. Lynell Powell

Dr. Lynell Powell had been an educator for 20 years. During this time, she has served as an elementary teacher, professional learning specialist, school administrator, and educational consultant. Currently, Dr. Powell works at a teacher’s college in the area of curriculum & instruction. She is passionate about the topic of joy in schools. You can connect with her on Twitter @drjoy77:

One of the most profound descriptions of student agency that I have come across is from Sean Michael Morris (2017) who shares, “Agency does not give us power over another, but it gives us mastery over ourselves, and an education that does not encourage or facilitate this agency is not an education. An education that convinces us of what needs to be known, what is important versus what is frivolous, is not an education. It’s training at best, conscription at worst. And all it prepares us to do is to believe what we’re told.”

Our educational system is not designed for students to experience true agency, that is, the freedom to choose what to learn and how to learn it. However, there is a more common understanding as it relates to a classroom setting which is that agency involves a continuous shift in the role of the learner. This shift is often illustrated on a continuum whereby students gradually move toward taking greater responsibility for their learning through the lens of components outlined by Bray and Mclaskey (2017) including voice, choice, engagement, motivation, ownership, purpose, and self-efficacy. On one end of the continuum, these elements are framed from a teacher-centered perspective and on the other end a learner-driven approach.

Let’s look for example at the idea of choice. In a classroom setting, a teacher might begin developing student agency by providing options for demonstrating knowledge of the content and gradually help students build the skills to not only choose those options but co-create them. Another example is the idea of motivation through the structure of goal setting. Teachers can assist students in creating academic goals, establishing a process that includes choosing resources to reach those goals, and incorporating structures to reflect on their progress toward those goals. It is most important to note that in any area the emphasis is on building students’ capacity over time by finding ways to shift the responsibility to them.

While there is no one exact guide that will address the needs of every learning environment, there are resources that support an understanding of how agency can be exemplified in the classroom. Bray and Mclaskey’s How to Personalize Learning offers concrete examples of how to move students along the learning continuum. Additionally, James Rickabaugh (2015) outlines five overall shifts to learner roles including:

Shift 1: From being skilled students to skilled lifelong learners

Shift 2: From having minimal impact on their educational path to co-creating the path they will take.

Shift 3: From being compliant learners to committed learners

Shift 4:From experiencing delivered instruction to experiencing instruction as a shared responsibility between learner and educator

Shift 5: From summative assessments designed to determine if learning has occurred to summative assessments that are a demonstration of mastery.

Developing student agency requires teachers to believe that their students are capable of independent thought. It takes a willingness to gradually release control and honor students as individuals.

References:

Bray, B., & McClaskey, K. (2017). How to personalize learning: A practical guide for getting started and going deeper. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

Richardson, W. (2019). Sparking Student Agency with Technology: Why should kids have to wait until after school to do amazing things with technology? Educational Leadership, 76(5)

Response From Dr. Felicia Darling

Dr. Felicia Darling is a first-generation college student who has taught math in grades 7-14 for 30 years. She leads workshops for K-14 educators and is author of Teachin’ It Breakout Moves that Break Down Barriers for Community College Students:

Students have agency when they have the freedom to explore their own voices and unique pathways to mastering the content. To foster student agency, educators can create inclusive, engaging learning environments where students feel safe to take risks, experiment, make mistakes, negotiate meaning, express their unique perspectives, and develop identities as powerful lifelong learners. This involves: (1) facilitating inquiry-based group learning; (2) delivering inclusive, equitable instruction; and (3) fostering a growth-mindset classroom. Below are 5 tips to support the first: facilitating inquiry-based group learning.

- Build Norms Together: Co-develop norms with students on the first day of class around group work. Scribe student responses to: “What do you like to have when learning in groups? and “What do you not like to have when learning in groups?” Incorporate their ideas into class norms and post the norms where they can see them every day. Including their voices when building norms will help them sense their agency.

- Include Group-worthy Tasks: Launching the first class of the year with a group-worthy task invites student agency early. Instead of lecturing on volume and then giving a worksheet, a teacher can introduce a group task, like “How many rectangular prisms can your group draw with a volume of 24cm3?” This task has multiple entry points, so students exercise choices around where to begin. Every time students make choices in the process of learning, they are developing agency. This task is open-ended and has multiple solutions, as well. Therefore, students have opportunities both to negotiate disagreement about solutions and to challenge their group’s assumptions—and really flex those agency wings. This task is low-floor, high-ceiling, too. This means that students with lower procedural fluency about volume can draw three figures and deepen their conceptual understanding of volume. At the same time, students with higher computational skills around volume will be motivated to think about volume in a more conceptual way and can challenge their assumptions by coming up with an infinite number of solutions.

- Use Participation Quizzes: Participation quizzes reinforce skills for successful group work in all grades. In the lower grades, teachers can circulate around the room and award group points when students: “lean in,” “have only one person talk at a time,” “get consensus on a question before asking the teacher,” or “use respectful talk to disagree.” In higher grades, teachers can provide actionable verbal feedback about skills that are working or not working for group work. Participation quizzes help to build that structure within which students can explore freely.

- Scaffold Learning: Think-Pair-Share and Think-Write-Pair-Share are scaffolds that prepare students to share in groups or whole-class discussions. Another scaffolding strategy is modelling how to disagree respectfully using a fishbowl activity. For example, one pair of students sit in the center of the room and model negotiating disagreement. Other students form a circle or horseshoe around them to observe. Pairs can take turns. Younger students need extra scaffolding to be successful in group work. They can use sentence starter and response A/B cards for building paired-conversation skills. Card A (for student A) says, “Why did you use the strategy of ______?” Card B (for student B) says, “I used _________ , because ____________?” Younger students may also benefit from assigning group roles like notetaker, timekeeper, reporter, and resourcer.

- Ask Open-ended, Probing Questions: It is important for teachers to resist the temptation to affirm that students’ answer are correct. Instead, respond to all students’ comments, reasoning, and perspectives with a consistent, “Thank you” or “Mmm Hmm” whether student responses are correct or incorrect. Also, paraphrase responses so students can hear their reasoning out loud, then respond, “Tell me more;; “What are the assumptions your group is making?;" and “Why do you disagree or agree with group #6.” Every time students have a safe opportunity to make choices, take risks, make mistakes, go down false paths, and find their way, it helps them to develop agency.

Response From Paula Mellom, Rebecca Hixon, & Jodi Weber

Paula J. Mellom is the associate director of the Center for Latino Achievement and Success in Education (CLASE). Rebecca K. Hixon is a postdoctoral research and teaching associate for CLASE. Jodi P. Weber is the assistant director of professional development for CLASE. CLASE is a research and development center housed within the University of Georgia’s College of Education. Together, they are the authors of With a Little Help from My Friends: Conversation-Based Instruction for Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CLD) Classrooms:

Agency is about choice and autonomy, but teachers often equate student choice with lack of structure that can lead to chaos. We often worry that the more involved our students are and the more they participate, the more risk there is that we will lose control! But there are ways to increase student agency and autonomy, while still meeting our instructional goals.

Choice need not lack structure and can in fact benefit from limits. We frequently say that structured limits open spaces for creative freedom—that is to say, too much choice can be paralyzing, while limited, structured choices can promote agency—but only when we know how to engage. Even when we provide students with opportunities to choose what to study and how to be assessed on instructional tasks that require critical and creative thinking, they often lack the tools to autonomously engage in them.

It is therefore imperative that we give them tools for autonomous interaction so that they might take more agency in their learning process. For example, we might create routines in the form of regular centers with familiar task structures that students have had modeled for them and have had the chance to practice. When task expectations are clear and explicit, and given to the students in a format that is familiar and routinized, students will gain confidence and become more autonomous in their interactions and agentive in their learning process.

Even kindergartners can engage autonomously in tasks if given scaffolded directions for authentic, relevant tasks as well as tools for productive collaboration (such as sentence stems) and the chance to practice them. It’s incredible to see 6-year-olds working through, for example, a “which one doesn’t belong” task, listening to each other and asserting their own ideas, using such phrases as “I agree with you because...,” “I respectfully disagree with you because...,” and “I hear what you are saying, but let me tell you what I’m thinking!”

But building agency isn’t just a matter of being presented with authentic opportunities and choice in their tasks. Students need to be guided through a regular, recursive process of intentional goal-setting and self-reflection in order to create self-regulatory habits. These habits provide the foundation for autonomously engaging in individual and collaborative group work and the means by which to tackle learning objectives, so students can begin to take ownership of their own learning.

Thanks to Laurie, Alva, Sarah, Keisha, Lynell, Felicia, Paula, Rebecca, and Jodi for their contributions.

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo.

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching.

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email or RSS Reader. And if you missed any of the highlights from the first seven years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. The list doesn’t include ones from this current year, but you can find those by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Best Ways to Begin the School Year

Best Ways to End the School Year

Student Motivation & Social-Emotional Learning

Cooperative & Collaborative Learning

Teaching English-Language Learners

Entering the Teaching Profession

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributors to this column.

Look for Part Two in a few days.