Last month I wrote about the Oakland Teachers Convention, which was convened by the Oakland Effective Teaching Task Force, of which I was a member.

One of the most powerful messages to emerge from this dynamic event was that teachers desire time and support for collaboration centered on their teaching practice. They also want to build on what is already working in the District, rather than bringing in costly consultants from elsewhere. Last week I attended an event at an East Oakland elementary school where nine teachers, who had engaged in teacher action research this year, shared their insights. This work, organized and supported by the Mills Teacher Scholars, based at the Mills College School of Education in Oakland, is a good example of the sort of teacher collaboration that improves outcomes for children, and strengthens teacher expertise. I asked program leaders if they would share a description of their work.

By Dr. Anna Richert, Claire Bove and Carrie Wilson

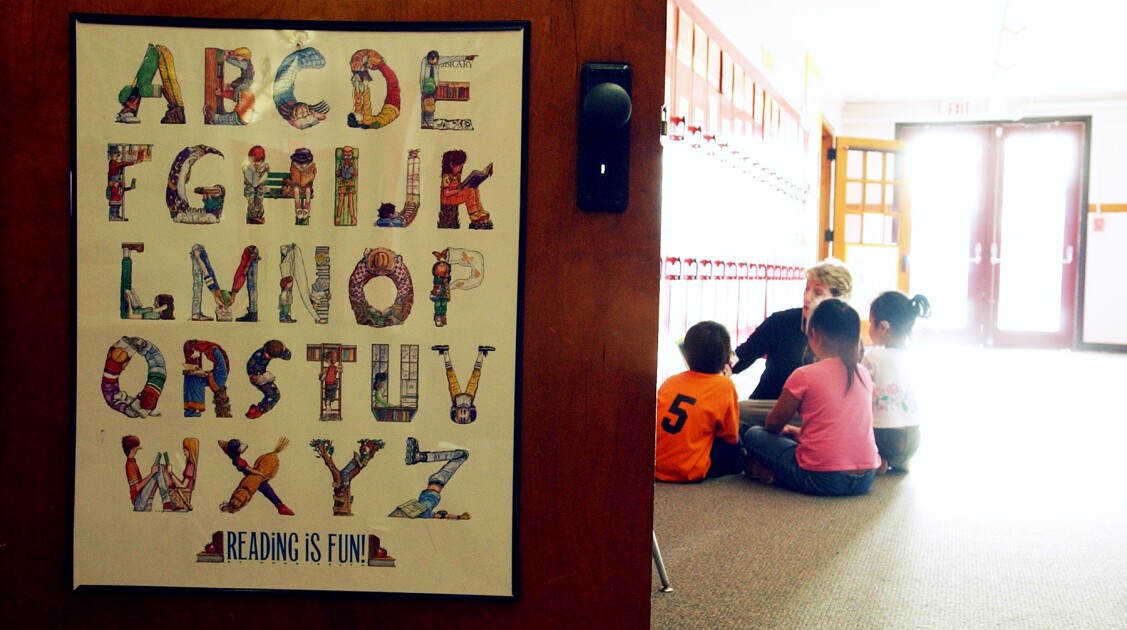

Recently two groups of Mills teacher scholars showcased their new understandings to their staff at New Highland Academy in Oakland Unified School District and at Roosevelt Elementary in San Leandro Unified. Teachers in both settings identified questions about their students’ learning and their own teaching practice to help them better address their diverse students’ learning needs. The process supported the teacher scholars to develop ways to “make their students’ learning visible,” which gave them a window into their students’ thinking.

Aija Simmons, a fourth grade New Highland Academy teacher explained at the outset of her project, “What I’m trying to figure out is: ‘what’s happening in a child’s head?’” Working with the Mills Teacher Scholars, Aija and her school colleagues met monthly in cross-grade level teams at New Highland Academy, a QEIA school (Quality Education and Investment Act) in the East Oakland flatlands. Each teacher selected a small group of focal students to focus his or her investigation. They systematically collected “real time,” everyday classroom data that they then analyzed with colleagues. The methodology allowed them to witness change over time.

The teachers reported that slowly and carefully over the academic year they developed a deep understanding about what their student know and are able to do. Working across grade levels brought insight to the progression of the students’ thinking not only over the year, but also across the grade span. Aija’s study provides a good example of how the inquiry process works. Her research focused on helping students make their reading process visible through the use of clarifying strategies, which she documented as part of her study. Designed to help student build their comprehension she introduced a set of strategies for students to engage with the texts they were studying. Her goal was to understand if, and how, these clarifying strategies affected her focal students’ ability to make sense of what they read. Throughout the process she monitored her students’ learning by routinely collecting various forms of data in the form of student work. She also interviewed students to hear their stories about what they were learning. These data, which Aija was able to collect as a routine part of her teaching day, allowed her to see what her students were doing and learning--and what challenges they encountered along the way.

Before using this data-driven approach to her practice, Aija felt her understanding was random at best. She explained:

My analogy is that I'm throwing darts at a target trying to hit it but I have no idea where the target is. Because unless you help the student to figure out how to make their thinking visible to you, you just keep giving reading lessons aimlessly throwing these darts out hoping you meet the target. So this research is an attempt to figure out where the target is.

In presenting her work on May 18th to her colleagues at the New Highland Scholars presentations, Aija explained how routinely collecting and analyzing student learning data allowed her to teach with intention. "[This year] I was never trying to figure out ‘what should I do for a reading workshop,” she explained. “Every time I looked at a data set and looked at what was emerging I knew exactly what to do for what kids...”

After the presentation to the staff, Aija wrote up her study to share to share it with others who were not at the presentations. She concludes her write-up by describing her classroom as a place where reading comprehension is a shared norm and her teaching moves are based on a clear understanding of what students need to encounter next. In comparing her teaching now with her approach before her research she writes:

My reading classroom is alive with clarifying conversations between my whole class, small groups, and even individual readers. Students are developing identities as comprehenders and clarifiers of text. I am teaching more targeted and strategic reading lessons. We are developing into more powerful readers. I say we because as this process happened I was becoming more aware of my own reading identity. Do I think I have the solution to my troubles of teaching reading comprehension? Not exactly. What I do have is a way to communicate effectively with my students about what they were thinking about a text and how they came to their conclusions. What I do have is a community of readers who no longer leery of saying, 'wait lets use a strategy because, I'm not understanding.'

What I have is a reading space alive with possibility and students who are now saying to me, 'we need more lessons on this because when I read that story, I couldn't figure out this strategy.' We have a process where I can guide the skills needed to help student comprehend and no longer just say sorry but 'that's not the main idea.

Teachers like Aija and her teacher scholar colleagues who are provided the time, space and support for pursuing questions they have about what and how their students know, are better prepared to help those students become the powerful learners they are capable of being. The responsibility for teaching all children well is then located in the hands of those who have the best chance of making school “work” for the children they serve. Let us draw on them to frame their path to building their professional expertise. Our best hope for improving student learning outcomes for all students is to create opportunities for their teachers to pursue what they decide they need to know to do their important work. The Oakland teachers have spoken up. Let us make this moment of change a reality.

If you are interested in learning more about this work, you may attend a special presentation of inquiry findings on Tuesday, May 31, 2011, at the Mills College School of Education Building, room 101, 5-8pm (see details here: //millsscholars.org/).

Anna Richert is a professor in the Education Department at Mills College, and Executive Director of the Mills Teacher Scholars. Clare Bove is a former science teacher, and the Associate Director of the Mills Teacher Scholars, and Carrie Wilson is also a former teacher, and the Associate Director of the program.

What do you think? Have you found action research of this sort to be a useful approach to improving your teaching?