It can be a jumble of red tape when a teacher moves states. The process of transferring a teaching license can feel bureaucratic, time-consuming, and overly complicated.

But a new analysis from the National Council on Teacher Quality, a Washington-based think tank, argues that in some aspects, state policies don’t go far enough.

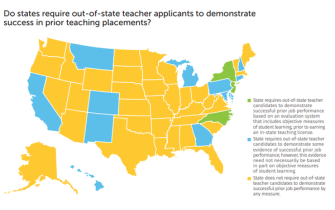

Just 16 states require incoming teachers to provide evidence of successful prior job performance. That could include teacher-evaluation ratings or a letter from a past employer, said Elizabeth Ross, the managing director of teacher policy at NCTQ and a co-author of the report.

Among those, only three states—New Jersey, New York, and North Carolina—and the District of Columbia explicitly require out-of-state applicants to show evidence that they have increased student learning and growth.

And while every state requires a criminal background check for a new in-state teacher-candidate, seven states don’t require out-of-state applicants to undergo a full background check as a condition for licensure. Those states are Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Mississippi, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Rhode Island. While the applicants may have already passed a background check at the start of their career, NCTQ notes that these states don’t consider how long ago the previous background check was conducted.

“States have a primary obligation to ensure that students are safe and secure, and a background check seems like a really straightforward mechanism to get that data,” Ross said.

New Jersey and Rhode Island do require out-of-state candidates to answer questions on their application about criminal history. Still, Ross said, “it seems plausible that you’d want some external verification that this individual is someone you’d feel comfortable educating children.”

NCTQ also found gaps between what states require from their incoming in-state teachers and from the out-of-state applicants.

For example, 19 states require all in-state aspiring elementary teachers to know the science of reading. (The cognitive research shows that students need systematic, explicit phonics instruction to learn how to decode words.) But only six states—Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Ohio, and Wisconsin—require specific evidence that out-of-state applicants understand scientifically based reading instruction.

A Complicated Process

“The process of transferring a teaching license is famous for its difficulty, often causing the teacher to forego a year or more of work,” said NCTQ President Kate Walsh in a statement. “So we were surprised to find so many states neglecting factors addressing effectiveness and student safety.”

Just a handful of states allow certified teachers to come from any other state and be considered fully licensed right away, a process that’s known as full reciprocity. Most states require incoming teachers to at least take some additional coursework or assessments. Even teachers who are certified by the rigorous National Board for Professional Teaching Standards have to take licensure tests when they move to 14 states.

Reciprocity requirements can be complicated and frustrating, and some teachers have left the classroom because of the red tape. Perhaps because of this, more states are trying to simplify the license transfer process, according to a 2017 analysis from the Education Commission of the States.

See also: How Licensing Rules Kept One Teacher of the Year Out of Public Schools (Opinion)

Indeed, the NCTQ analysis found that 14 states require all out-of-state teacher applicants to take additional coursework to prove content knowledge, without allowing a test-out option.

This could have a “chilling effect on the number of effective, experienced teachers who may be interested” in teaching in their new state, Ross said.

Nineteen states make it harder for an out-of-state applicant to qualify for a teaching license if they were prepared to teach through an alternative route. Teachers who did not go through a traditional teacher-preparation program might have to take additional coursework or satisfy additional student-teaching or internship requirements.

NCTQ points to the District of Columbia as having among the strongest licensure requirements for out-of-state teachers. Teachers have to submit evidence of two years of effective teaching experience, complete a criminal history background check, and submit their prior content test scores. If they didn’t pass the appropriate licensure tests, applicants will have to pass the District of Columbia’s assessments—but there are no additional coursework requirements.

D.C. “walks the fine line between maintaining a high bar but not creating an additional burden that is not related to whether the teacher is going to be effective in the classroom,” Ross said.

NCTQ recommends that other states follow D.C.'s lead as they consider their licensure processes.

“As our country becomes increasingly mobile, I think it’s an area that really behooves states to focus on,” Ross said. “We want to make teaching the most attractive profession.”

But when teachers are faced with these barriers to teach in another state, she said, transferring a license “becomes not worth doing.”

Chart via NCTQ