The House GOP’s plan to overhaul the tax code includes a provision that would allow 529 college savings plans to be used for K-12 expenses, including private school tuition. It’s a victory for advocates of school choice that we previewed last August—but who uses those accounts now, and how much could they help expand choice?

Just a quick overview: 529 plans are state-backed savings plans that can cover college tuition and other costs related to higher education. Unlike some other tax-advantaged plans, various family members can open accounts on behalf of a child. Contributions to 529 plans are tax deductible. There isn’t a single hard cap on how much people can contribute to 529s, although they’re supposed to only pay for qualified education expenses. More basic information here via Business Insider.

Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos also praised the provision of the bill as “a strong and proven tool to help make education more affordable for middle-class families.” (Remember that the school choice expansion plans she pushed for in the proposed Trump budget have fallen flat in Congress.) But ironically enough, the American Federation for Children, the school choice advocacy group that DeVos used to lead, said while it supported the move, it wouldn’t truly help “low-income families who aren’t able to put away those savings.” EdChoice, formerly known as the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, expressed pros and cons for the idea similar to DeVos’ old organization.

Will the GOP Tax Bill Help More Families Exercise School Choice?

So what do we know about the people and numbers behind 529 plans?

The average value of the savings account was $19,800, the Chronicle of Higher Education reported in 2015. About two years ago, assets in 529 plans stood at $258 billion, according to one estimate, according to CNBC, an increase over previous years. And there were 12.3 million open 529 accounts, a number that also grew from 2014.

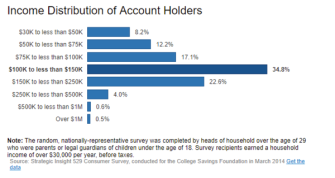

However, the same CNBC story found that the number of families using the plans dipped slightly, from 29 percent in 2014 to 27 percent in 2015. And 57 percent of account holders were from households making $100,000 to $250,000 annually, as a 2014 survey the Chronicle of Higher Education highlighted:

While awareness of 529 plans might be growing, it’s not clear that the absolute level of awareness is all that high. A 2016 survey by Edward Jones, an investment firm, found that 72 percent of Americans weren’t aware that 529 plans existed. While 46 percent of households earning more than $100,000 in annual income could correctly identify a 529 plan, only 18 percent of households earning less than $35,000 annually could do so.

Ryan Cooper at the Week savaged 529s in a 2014 piece, calling them “utter trash policy” that mostly benefit the wealthy, and are also very vulnerable to market fluctuations. He highlighted Kansas, where 81 percent of 529 benefits went to families making more than $100,000, as an example of how 529 plans goosed richer Americans’ bottom line.

Cooper also raised a problem for 529s with respect to higher education prices that might, in theory, apply to K-12 costs: the temptation 529 plans create for colleges to jack up tuition and other costs, “creating a vicious cycle of price gouging and desperate saving.”

Jessica Thompson, the policy and research director at the Institute for College Access and Success, which focuses on helping low-income and first-time college goers access and succeed in higher education, said the 529 proposal does incentivize behavior through which a family might use a 529 to save for a private school, but thereby save less for that student’s college tuition.

“It incentivizes something that may not be in the best interest of their families,” she said, adding that for wealthier families that can save for both K-12 and higher education, “it’s just a giveaway, to be frank.”

In the same tax bill, the GOP would also get rid of Coverdell accounts, tax-free savings vehicles for K-12 expenses up to $2,000 annually for a single beneficiary. On the one hand, this means that 529 accounts would “cannibalize” Coverdell in the tax proposal, said Bob Williams, the senior vice president and managing director of the Simmons First Investment Group in Little Rock, Ark. who works with 529 plans. But on the plus side, it means more flexibility for those 529 accounts, which are tax-deductible, not just tax-deferred like Coverdell accounts.

“Generally, I’m working with high net-worth individuals” who use 529s, Williams said.

In addition, parents might have less time to accumulate savings in the 529 plans for K-12 than they would for college. That’s especially true for those who might want to send their children to private schools in the earliest grades.

“Traditionally, the time value of reinvested fund adds substantially to the value of the investment,” Williams said.

The idea has split Washington wonks who back school choice.

The increasing value of 529 plans in recent years reflects a growing awareness of the plans, said Lindsey Burke, the director of the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank that likes the 529 expansion idea. That means it could open up the school choice playing field significantly, she indicated.

But Michael Petrilli, the president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a big school choice backer, looked at the landscape of 529s (along with the GOP’s tax plan overall) and came away unimpressed with their ability to expand school choice to low-income students.