One hundred fifty years ago today, the first shots were fired in the Civil War, a bloody conflict that pitted brother against brother and set the stage for issues that still resonate. That anniversary is inspiring a vast array of initiatives and activities spanning the next several years. It offers a rich opportunity for students (and everyone else) to learn more about the seminal American conflict. And it gives Education Week an excuse to probe the war from the perspective of teaching and learning.

I’ll start by noting an interesting political dimension. Fort Sumter itself, the site of the first shots, was hours away from being forcibly closed Friday night, before lawmakers and President Obama struck a budget deal to avert a government shutdown.

Anyway, back to education. More than half the states have formed commissions to organize and coordinate their sesquicentennial efforts, from Alabama and Virginia to Vermont, Wisconsin, and Oregon, according to the American Association of State and Local History. The AASLH includes a list on its website.

The Virginia commission, for example, intends to promote “inclusiveness” in the commemoration, its website says. It will “seek to portray a balanced story of Virginia’s participation in the American Civil War that includes stories from African-American, Union, and Confederate perspectives; battlefront as well as home front; slavery and freedom; and the causes of the war and its enduring legacies.”

In fact, the state produced a three-hour, educational DVD on the Civil War, tackling such issues as slavery, the life of soldiers, and major battles. It provided a free copy to every public school in Virginia, as well as public libraries. Also as part of its sesquicentennial commemoration, the state supported the development of the Civil War 150 “HistoryMobile,” a traveling exhibition that will provide “an interactive and immersive experience that will help visitors better understand the challenges faced during the Civil War by soldiers, civilians, and slaves, and will present the losses, gains, and legacies of the Civil War in Virginia,” according to the commission.

It’s probably worth noting, that the Civil War is not only important to Virginia from an historical and educational perspective. It’s also big business, given the state’s many tourist attractions connected to the conflict.

At Education Week, we’re planning a special package of stories on the Civil War, expected out Friday. One issue we’ll examine is how teachers are using primary sources and technology to bring the conflict to life for students and help them gain a deeper understanding. A ton of materials are now easily accessible online, for example, even as people tell me the age-old school field trip to battlefields and museums is alive and well.

Here’s what Garry Adelman, the director of history and education at the Civil War Trust, had to say about the value of primary source materials.

“There is something about the authenticity of the real thing—a letter, an ordinance, a battlefield or photograph—that moves people, and often makes them want to come back for more,” he told me in an interview. “They all bring home the complexity of the Civil War. People understand that these people weren’t in black or white.”

Or, here’s what Carole L. Parsons, a 5th grade teacher from Aiken, S.C., said: “When I first started teaching, it was the textbook. That was all we had. ... Today, the Library of Congress and National Archives alone can give you tons and tons of stuff.”

She added: “It gives students a different perspective. It’s not just this guy living in our time telling us about the war. This is a photograph, a diary entry, a map that one of General Sherman’s soldiers drew.”

I can’t begin to cite all the inspired examples I’ve come across of using primary sources and technology to enhance learning about the Civil War. I’ll just mention one here. Last week, I saw firsthand a group of 6th graders from Stonewall Middle School making short videos at Manassas National Battlefield Park. They conducted research, wrote scripts, made props, acted, directed. And when they’re finished, many will head to the editing room during spring break. Pretty cool. (This is a project spearheaded by The Journey Through Hallowed Ground Partnership.)

As part of the EdWeek coverage, we’ll also take a closer look at how, from a content standpoint, the Civil War is taught today. It’s always hard to make generalizations, but we’re doing our best by interviewing teachers, scholars, and others, looking at sticky issues, any regional variations, state standards, etc. Certainly, one issue that still drives significant public debate around the country is the causes of the Civil War, even as most historians seem to agree that slavery was the leading driver.

“Slavery is the major cause of the Civil War,” James I. Robertson, a prominent historian of the war and a member of the Virginia sesquicentennial commission, told me. “Anyone that denies that is a bad student of history.”

That said, Mr. Robertson and plenty of others emphasize that slavery was by no means the only issue behind the war, and that it was tangled up with all kinds of other matters, such as the economy and states’ rights. And experts caution that slavery’s centrality to the war does not mean that somehow an assessment of the war should conclude that the “North was good” and the “South was bad.”

“You have to understand that slavery was sectional, but racism was national,” Paul Anderson, an associate professor of history at Clemson University who has worked extensively with teachers, told me. In professional-development workshops, he said he cautions teachers: “Don’t come to the classroom thinking this is a moral crusade [by the North]. It isn’t. ... War is a complicated mess.”

I should say that primary sources, of course, are an excellent way to better understand the causes of the Civil War. Here, for example, is the South Carolina secession declaration. And here is the so-called Cornerstone Speech delivered by Alexander Stephens, the vice president of the Confederacy.

Those issues, aside, perhaps the biggest challenge in teaching the Civil War today may well be time, or a lack thereof. My interviews suggest that the time teachers typically spend on the Civil War in history class can be pretty limited, ranging from three days to a week or two, though I did hear of cases where it might get even two months.

The problem with time constraints in busy U.S. history survey courses is that it’s hard to delve deeply into the many complex issues the Civil War brings up. Also, I imagine if you’ve only got a few days, it might be harder to pull off some of the more engaging uses of primary sources. (And that can be especially hard if the Civil War and Reconstruction come up, as they often do, at the end of the semester, when students are perhaps more easily distracted.)

There’s lots more I could say on teaching the Civil War, but I’ll stop here for now.

In two previous blog posts, here and here, I’ve included some useful resources for those looking to learn more about the war, especially educators. I’ll include a few more here:

• TeachingHistory.org has a section with lots of Civil War resources (more than 10,000 documents and monographs);

• The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History also hosts a special Web page on the Civil War; and

• The National Park Service has a Web page on the sesquicentennial.

Know of any other helpful resources? Post a comment and let us know about them.

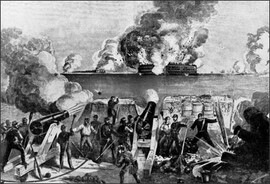

Image: A 19th-century painting depicts Confederate artillery on Sullivans Island, S.C., firing on Union troops at Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861.

AP Photo