Welcome returning guest blogger Chris Kukk, Ph.D. Professor of Political Science at Western Connecticut State University, a Fulbright Scholar, founding Director of the Center for Compassion, Creativity and Innovation.

A holistic learning environment fosters a balanced approach for developing the intellectual and social-emotional strengths of students. According to a recent study by Harvard’s Graduate School of Education, “Almost 80 percent of students [rank] achievement or happiness over caring for others.” We need such a balance more than ever and a compassion-based education provides an effective approach. Integrating compassion into classrooms can strengthen the emotional, intellectual and social learning environment of a school.

Strength and Compassion Defined

Miriam Webster defines strength as “the quality that allows someone to deal with problems in a determined and effective way.” Compassion is strength and there is strength in compassion. I define compassion as a holistic (360 degrees) understanding of a problem or suffering of another with a commitment to act for solving the problem or alleviating the suffering. Weaving compassion with strength produces what Mister Rogers (the sweater-vested childhood hero and educator of my youth) called “real strength”. He observed “Most of us, I believe, admire strength. It’s something we tend to respect in others, desire for ourselves, and wish for our children. Sometimes, though, I wonder if we confuse strength and other words--like aggression and even violence. Real strength is neither male nor female; but is, quite simply, one of the finest characteristics that any human being can possess.” Compassion-centered schools build “real strength” by creating an emotional, intellectual and social learning environment that fosters academic success and mental stability.

Compassion and Resilience

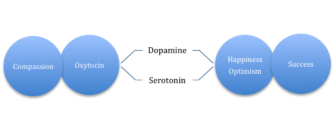

A compassion-centered school increases a person’s sense of resiliency. The research of Shawn Achor, Dacher Keltner, Tania Singer and Paul Zak and others demonstrate the neuroscience effect of having compassion at the forefront of a person’s thinking is positive on both the individual and communal levels. The effect, in rudimentary form, is that when a person thinks from a compassionate mindset, he or she releases the peptide hormone oxytocin, which then activates the neurotransmitters of dopamine (brain reward) and serotonin (anxiety reduction) contributing to happiness and optimism--two characteristics that contribute to success and resiliency (see the diagram below).

Having classrooms humming with oxytocin can help reduce stress levels, hopefully also reducing the perceived need for stress-reducing drugs. The American Psychological Association’s (APA) 2013 Stress in America report found that eighty-three percent of teens cited school as a source of stress and their reported level of stress is higher than adults for the first time since the APA study started. With a 41% increase in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) diagnoses of school children over the last decade (that is an estimated 6.4 million children with over two-thirds of them receiving prescription drugs), shouldn’t we be focused on what we can do to change a school’s environment for learning (i.e., including “passion projects” and “Genius Hour”) instead of altering or adding to a child’s drug prescription for behavior?

Orchids and Dandelions

A compassionate and positive school environment (a ‘compasitive’ environment) strengthens cognitive abilities. A compasitive learning environment fosters the release of dopamine in the brain, which helps students retain the information they learn. Neuroscience research has shown that if a student has low dopamine levels his or her ability to retain information weakens. Scientists label children with naturally low dopamine levels (due to a variant in a gene known as DRD4) as “orchids” and others as “dandelions.” While dandelion children can adapt and develop in any type of environment, orchid children are “context-sensitive.” Bruce J. Ellis and W. Thomas Boyce report that for these children “survival and flourishing is intimately tied, like that of the orchid, to the nurturant or neglectful character of the environment.”

Various peer-reviewed studies clearly demonstrate that negative and uncompassionate home and school environments hurt the social-emotional and intellectual development of orchid children but have minimal to no effect on dandelions. However, the studies also show an amazing effect that compasitive homes and schools have on both orchids and dandelions: while both orchids and dandelions succeed in a compasitive environment, the orchids thrive to such an extent that they surpass the dandelion children in social-emotional and intellectual learning. In other words, compassionate and positive school environments help all children succeed and they turn a potential learning deficit into an asset.

Compassion is Education’s Water

Structuring a classroom where cooperation among students is given at least equal time as competition can also increase learning. A method called ‘learning-for-teaching’ not only increases cooperation in class but it improves conceptual retention. Matthew Lieberman cites the method in Social: Why our Brains are Wired to Connect to show that when students learned “material in order to teach it, [they] performed better on what to them was a surprise memory test [as] compared to those who knew the memory test was coming and had studied for it.” The reason, according to Lieberman, is that when students believe that their actions are helping others, they learn more efficiently and effectively; Lieberman calls this the social encoding advantage. Schools could take advantage of social encoding by becoming schools of compassion; I wonder what the effect on bullying would be?

The idea of compassionate schools sometimes causes critics to say that the entire concept is nice but too soft and therefore not powerful enough to make a difference into today’s world of education. The soft argument, however, doesn’t hold water when reflecting upon the words of Lao-Tzu: “Water is fluid, soft, and yielding. But water will wear away rock, which is rigid and cannot yield. As a rule, whatever is fluid, soft and yielding will overcome whatever is rigid and hard. This is another paradox: what is soft is strong.”

Compassion is education’s water; it not only can help quench the thirst for social-emotional learning but it can cut through the rigidity of standardized-test based education to foster holistic learning. A compassion-based education is not focused on filling-in-the-blanks; it is focused on filling in the person. Compassionate classrooms are sources of ‘real strength’ in education for ‘what is soft is strong.’

Resources:

American Psychological Association, “Are Teens Adopting Adults’ Stress Habits?” Stress in America 2013 (11 February 2014).

Bruce J. Ellis and W. Thomas Boyce, “Biological Sensitivity to Context,” Current Directions in Psychological Science Vol. 17, no. 3 (June 2008)

Stephen P. Hinshaw and Richard M. Scheffler, “How Attention-Deficit Disorder went Global,” The Wall Street Journal (March 12, 2014): A19.Kai Kupferschmidt, “Concentrating on Kindness,” Science, vol. 341 (September 20, 2013): 1336-1339.

Matthew Lieberman, Social: Why Our Brains Are Wired to Connect (New York: Crown Publishers, 2013).

Rick Weissbound, Stephanie Jones, Trisha Ross Anderson, Jennifer Kahn and Mark Russell, “The Children We Mean to Raise: The Real Messages Adults are Sending about Values,” Making Caring Common Project (Cambridge, MA: The President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2014).

Follow Chris on Twitter @DrChrisKukk