By Amanda Avallone, Content Manager for Next Generation Learning Challenges

[Social capital is] the sum of the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of relationships possessed by an individual or social unit. --Janine Nahapiet and Sumantra Ghoshal in “Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage.”

“It’s not what you know; it’s who you know” has long been an adage in the context of adult opportunity. Come to find out, it’s especially true for young people embarking on the “wayfinding decade” after high school. A growing body of research in the fields of education and sociology points to the vital role of social capital in students’ lifelong success.

For many decades the focus of K-12 education has been on knowing the what of academic content and skills. Meanwhile, much of the who of supportive relationships, resources, and networks has been the domain of outside-of-school experiences like clubs, community activities, and summer pursuits like camp, volunteer projects, or paid work. Moreover, as with other types of capital, access to social capital is not evenly distributed across our society. In fact, research suggests that lack of social capital may be the most important limiting factor in economic mobility.

This Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning is devoted to the concept of social capital and its implications for educators. Specifically, this edition will explore:

- Why social capital is an essential part of young people’s preparation for life

- How developing social capital is aligned to issues of equity

- The ways schools and educators can support students in acquiring social capital

The Why of Social Capital

[Social capital] enables us to create value, get things done, achieve our goals, fulfill our missions in life, and make our contributions to the world...No one can be successful--or even survive--without it. --Wayne E. Baker, University of Michigan Ross School of Business

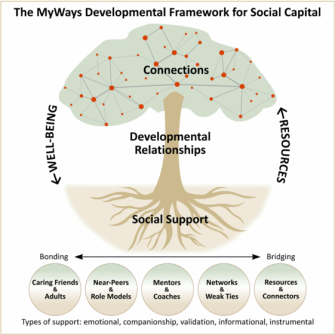

In counterpoint to cultural myths like the “self-made man” and the “rugged individualists” who make it entirely on their own, social capital recognizes the key roles played by supportive others in our lives, both for bonding (emotional support, companionship, and validation) and for bridging (informational and instrumental support). In other words, social capital promotes personal well-being and provides access or bridges to resources outside the self.

To test this idea, consider your own experiences: who in your life supported you--emotionally and materially--to become the adult you are today? Consider family, friends, coaches, teachers, mentors, employers, institutions, and weak-tie acquaintances and professional connections. Cultural myths notwithstanding, we are all embedded within a multi-layered ecology of connections and relationships.

In 5 Essentials of Building Social Capital, Report 4 in NGLC’s MyWays Student Success Series, this social capital ecosystem is depicted as a tree. Similar to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the roots of the tree represent the social supports that sustain well-being and growth. They serve as the foundation of trust and reciprocity on which mutually beneficial relationships can be built. The trunk of the tree corresponds to adult relationships that foster young people’s self-exploration, growth, and engagement with the larger world. The branches symbolize the complex, ever-evolving, and mutually beneficial network of connections that our students can harvest for resources to accomplish their goals.

Especially in an era of complexity and constant change, social capital is a key differentiator for success in education and career, as well as for personal satisfaction and wellbeing. A challenge for educators is to create new structures and experiences that will empower young people to build and expand their own social capital.

Social Capital and Equity

[M]iddle-class parents do not operate alone, but are embedded in the social network of institutions, school personnel, institutional agents and youth-serving organizations in the community... In contrast, children in segregated, stratified communities face a “constricted social universe.” --Ricardo D. Stanton-Salazar, in A Social Capital Framework

According to sociologist and researcher Ricardo D. Stanton-Salazar, adolescents of every background require a robust ecosystem of social capital--not just a best friend, caring neighbor, or supportive teacher-- but an entire “network of socialization agents, natural or informal mentors, pro-academic peers, and institutional agents [high-status, non-kin individuals] distributed through the extended family, school, neighborhood, community, and society.”

However, as his research shows, social class exerts a strong influence on students’ network ecology: young people from higher class positions are much more likely to be embedded in social networks with access to people of high status with highly valued societal resources. The lower a student’s social class, on the other hand, the more constricted the social universe and the less likely it is that they will acquire the social capital they need. The result, according to this research, is “social reproduction of class inequality.”

Let us revisit for a moment the mental list of your own social capital assets, the supportive people you considered above. How broadly accessible are those experiences and, consequently, the relationships you forged while participating in them? How many took place outside of school? How many had associated costs or other barriers to entry?

According to Stanton-Salazar, what is needed are counter-stratification strategies that enable students to build durable social capital. Schools have a pivotal role to play in this effort. In fact, he argues that, unless schools restructure themselves to widen and strengthen students’ networks during their K-12 years, schools will only perpetuate and deepen class segregation and the opportunity gap.

How Educators Can Help Students Build Social Capital

As the term “5 Essentials” implies, all five of these dimensions are necessary, and educators can be instrumental in supporting each one of them, either directly through their relationships with students or by facilitating students’ connections to other adults in the wider world.

ImageThe MyWays 5 Essentials for Building Social Capital

Caring Friends & Adults. According to the Center for Promise’s Don’t Quit on Me, the presence of a single trusted adult appears to be a necessary component of support...Some young people may be standing in a room that contains all the support they need, but they need someone else to turn on the lights so they can see what’s there and reach for it.”

Many students find that trusted adult at school--an educator, counselor, or coach who can forge a strong relationship and then, once trust is established, connect the student to a web of other supportive adults. This is a traditional role for educators, and it is as important for student well-being as it ever was.

Near-Peers & Role Models. In adult life we constantly learn from those who have greater expertise or are more advanced than ourselves. In contrast our schools tend to deny younger students access to an abundant social capital resource: the older students who share the building with them. Robert Halpern, in his analysis of the current learning landscape, warns of a “peer world” bubble based on age, which can delay and detour young people from their natural exploration and entry into the adult world.

School models--and individual educators--can foster near-peer relationships through mixed age classrooms or ongoing cross-grade opportunities, including mentoring and mixed-grade electives, clubs, and projects. Some schools and districts take this a step further, exploring, for example, how competency-based education (CBE) can develop this social capital essential as a key element of whole-school design. In a multi-age environment based on competency, not grade level, learners in these schools regularly work on projects with students of different ages, as well as their peers.

Mentors & Coaches. Outside-of-school mentoring programs, especially ones targeting young people of color or those from families with low incomes, are a well-established component of youth development. However, as this research study indicates, the adolescents in most need of mentoring and coaching, particularly those of working-class backgrounds, are least likely to have access to mentors or know how to find one.

One innovative and promising approach that strives to address these limitations is Youth Initiated Mentoring (YIM). Unlike traditional models in which young people are matched with volunteer mentors, the YIM model trains youth in mentor-recruitment strategies and then asks them to nominate mentors from among the non-parental adults who are already part of their social networks (e.g., teachers, coaches, family friends, and extended family members).

YIM’s success has implications for schools: although teachers and coaches can certainly act as mentors for individual students, they can also provide all young people with the skills they need to identify and establish relationships with mentors from their own social networks, a capability that will serve students well throughout their lives.

Networks & Weak Ties. For young people of all backgrounds, developing ties to adult networks and acquaintances is perhaps the scariest of the “5 Essentials” for building social capital. As Paulina Billett, a specialist in youth social capital, points out, adolescents are developmentally attuned to deepening relationship bonds, but they often have less appreciation for the bridging kinds of relationships that allow them to gain access to informational, financial, material, and service resources.

In addition, Stanton-Salazar’s work with Latino and Latino-American youth explores how contextual factors in students’ lives can lead to mistrust and wariness. Over time, he finds, some youth adopt a posture of “unsponsored self-reliance” that manifests in avoidance strategies when it comes to interacting with certain adults, even those who could help them.

For these reasons, students might require more scaffolding to develop their own networks and weak ties. Some project-based learning models, for example, not only partner with industries and community organizations, but they also provide students with training and support in how to communicate with non-parental, non-educator adults.

Resources & Connectors. Young people are more empowered to learn and advance toward their goals when their environment is populated by “more connected others” who can help bridge to resources that would otherwise be unavailable.

To afford students more opportunities to make these kinds of connections, many forward-thinking schools are intentionally “porous.” With community partnerships as a core design element, they provide instruction and practice in building social capital through internships, industry mentors, field experiences, and real-world projects.

Resources

- “Opportunity, Work, and the Wayfinding Decade,” Report 1 of the MyWays Student Success Series, examines market shifts that have transformed the journey from high school to gainful employment into a highly complex and risky wayfinding decade for today’s youth.

- “5 Essentials in Building Social Capital,” Report 4 of the MyWays Student Success Series, explores five types of social capital young people need to secure social support, developmental relationships, and connections to resources.

- Wayne E. Baker’s “What is Social Capital and Why Should You Care About It?” the first chapter of Achieving Success Through Social Capital, defines social capital and explains why it is vital for success in adult life.

- Center for Promise’s Don’t Quit on Me focuses on the importance of relationships with stable, caring adults in helping young people stay on track toward graduation and career.

- Robert Halpern’s Youth, Education, and the Role of Society examines the “learning landscape” currently available to our nation’s adolescents and the need to expand, enrich, and diversify the learning opportunities available to them.

- “Youth Initiated Mentoring: Investigating a New Approach to Working with Vulnerable Adolescents” in American Journal of Community Psychology describes YIM and presents research findings related to this innovative mentoring model.