It’s easy to complain about laws and policies we don’t like, much harder to craft policies that make complicated systems function effectively. When it comes to federal education law and policy, we’re beginning the transition from No Child Left Behind to the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). The new federal act calls on states to gather stakeholder input as they develop a state plan for ESSA implementation, and last week, I had the opportunity to participate in that process. At the end of this post there’s more information for Californians who want to be involved.

Here are some of my takeaway thoughts and observations from the experience.

Where are the teachers?

At the start of the meeting, our facilitator from the California Department of Education (CDE), Barbara Murchison, asked the 40-50 people present about our job description. There were only two teachers in the room. Later in the event, the number of attendees had grown with some late arrivals, so I don’t know if the number of teachers increased, but it still wasn’t enough. Most of the participants were district level staff and administrators, those who have the direct responsibility for following the laws and reporting to the CDE. I was glad to see that one of the questions from the CDE was how to improve outreach, and I hope they’ll follow some of our suggestions. Those of us in attendance had learned about the meeting through an email from the CDE, and I would imagine very few teachers subscribe to CDE email lists. We suggested that the CDE needs to reach out directly to stakeholder groups through our professional associations and unions.

As for parent and student input and feedback, we asked if and when that would be part of the process, and were assured that the CDE has heard about the need to expand its stakeholder dialogue as the process continues.

I would also suggest to my teaching peers that more of us need to be proactive in seeking opportunities to influence policy, and participate in policy discussions at every level.

The California Way

In recent years, California has adopted or held on to a variety of education policies that have put our state at odds with federal education policy and priorities coming out of the Obama administration, especially during Arne Duncan’s leadership at the Education Department. Race to the Top and NCLB waivers pushed states to pursue a variety of policies - mainly around testing and the use of test scores - that California resisted, and wisely so. My fellow EdWeek blogger, Charles Taylor Kerchner, writes the “On California” blog and has written frequently about “The California Way” - education policy that has emerged during the leadership of three top officials in the state: Governor Jerry Brown, State Superintendent Tom Torlakson, and State Board of Education President Mike Kirst.

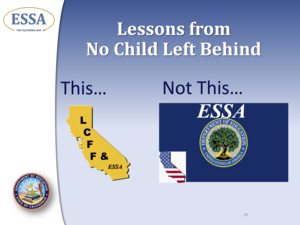

California education policy underwent a significant revision of its own with the creation of the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) and Local Control Accountability Plan (LCAP). The presentation from the CDE to stakeholders suggests that the department intends to maintain these policy directions and priorities, with ESSA as the secondary focus. This slide from the CDE presentation (right) gives you the general idea in a visual format. I’ve heard Mike Kirst speak about state education policy many times. He has fifty years of professional experience in the area, and one idea he has emphasized in recent years is that we need to take a slow and humble approach to policy implementation. He’s been around long enough to understand that there are no lightning quick transformations, no miracles in fine print of ESSA or state ed. code or the Common Core.

Consensus around equity and diversity

In the break-out group conversation that I was part of, our answers to the CDE’s open-ended questions often came back to the ideas of equity and diversity. It was good to see these imperatives called out numerous times, by multiple participants. Equity emerged as a goal and a metric for state accountability in providing services and personnel to underserved and high-needs student populations. The state’s new funding formula already aims to address inequities, and our group pushed the idea further. One important perspective was that small and rural districts face even greater challenges in providing for their students, as they have smaller labor pools, and greater expenses when it comes to many professional development activities. Funding provided to small schools and districts on a per-pupil basis is often inadequate to cover expenses for any professional activity that involves any travel for staff or for outside consultants or trainers.

We also discussed the lack of diversity among teachers and administrators, and suggested that the CDE should set goals and take actions that will increase the number of teachers and education leaders who are people of color. I was pleased to see this emphasis emerge repeatedly from a group of predominantly white educators.

Is it all about the money?

Within half an hour, I’m sure my group had generated a several billion dollars in hypothetical spending to improve public education in California. School staffing was an issue of great concern, with California at or near the bottom in many staffing categories. More professional development came up, of course - not only for teachers, but for all school staff, and especially school leaders.

What can schools do that’s relatively inexpensive? Does every improvement involve money? We agreed that there are some steps that schools and districts can take to improve without a huge increase in spending, but from the state level, the main way to encourage creative problem-solving is to provide more policy flexibility. Some participants in our group worried that there’s already too much flexibility, and that the state’s policy pendulum has lurched too far towards local control, after a period that many people felt was characterized by excessive state regulation. Where we used to have dozens of categorical funding streams, we now have flexibility, but some in our group felt that categorical regulations provided necessary protection for certain priorities.

Can you focus too much on literacy?

Some members of my group suggested that literacy should remain a distinct and essential focus of state education policy, since literacy is the foundation of learning across disciplines and subjects. Without disagreeing about how essential literacy is, I questioned whether there are risks in over-emphasizing literacy at the policy level, fearing that we’d see inequities in the quality of curriculum and learning experiences for students whose literacy skills lag their peers. More specifically, if a school in an under-resourced area has students with lower reading scores, are we going to repeat the mistakes of the past, subjecting these students to an over-emphasis on reading skills instruction that minimizes other learning experiences? Are lower-scoring students going to be given a steady diet of programmed, decontextualized reading instruction, while higher scoring students, often in schools with greater resources already, get to experience a wider variety of enriching activities? We know that literacy depends upon knowledge, not just the ability to decode. Do students in disenfranchised schools and communities get to read about enriching experiences, while students in affluent communities get to have those experiences? I’m not a literacy expert, but I worry that if we overemphasize reading scores, creating pressure to generate certain gains measured in certain ways on a certain timeline, we’ll just repeat the errors of NCLB and perpetuate inequities rather than fix them.

Specific, concrete policies that work

Frequently in our discussion, a facilitator from the CDE asked what the department should do. Yes, we want more money, greater equity, better curriculum and instruction, but what can a state agency do to promote those goals through a state plan based on federal policy? I had two suggestions.

Restore state support and incentives that increase the number of National Board Certified Teachers, especially in districts and schools where the needs are greatest. The certification process improves teaching, and improves teachers’ capacity for productive collaboration and leadership. (Disclosure: I work on a blogging project for the National Board).

Build on the idea of the Instructional Leadership Corps (ILC). This model for professional development puts teachers in charge of helping teachers grow in the profession. We become less reliant on non-teaching consultants, less reliant on expensive curriculum developed by the mega-publishers in the textbook industry. Developed through a collaboration involving union and university-based partners, the ILC was conceived to support the Common Core transition, but it simply makes sense as an approach to improve teaching and learning. The next iteration should move away from reliance on philanthropic support and empower teacher leaders as part of a sustainable and scalable evolution of our educational system.

The California Department of Education organized six regional meetings to present information about ESSA and to hear from education stakeholders. As of this writing, there are three remaining meetings for my fellow Californians interested in this process. (Click here for registration details).

- June 27 Tulare County

- June 28 Los Angeles County

- July 8 San Bernardino County

There’s also an online survey for Californians to send input to the Department of Education. You might want to review the slides from this presentation before answering the survey questions.