(This is the second post in a three-part series. You can see Part One here.)

The new question of the week is:

What are the best ways to organize and lead classroom discussions?

Part One featured responses from Rita Platt, Adeyemi Stembridge, PhD, Jackie Walsh, Doug Lemov, and Valentina Gonzalez. You can listen to a 10-minute conversation I had with Rita, Adeyemi, and Jackie on my BAM! Radio Show. You can also find a list of, and links to, previous shows here.

Today, Kara Pranikoff, Laura Robb, Sky Sweet, Tricia Ebarvia, and Patty O’Grady contribute their commentaries about facilitating classroom discussions.

Response From Kara Pranikoff

Kara Pranikoff is a literacy coach at a public school in New York City. She has recently published a book, Teaching Talk: A Practical Guide to Fostering Student Thinking and Conversation (Heinemann, 2017) that shares many ways to keep the balance of classroom discussion in the hands of the students:

As a community of learners, we need to develop structures to share ideas and learn from each other. Often it is easier to turn over our small group or partner talk times to student discretion. We know we can’t be present in all these smaller arenas so we feel confident stepping back and letting students talk and respond to each other. However, if we believe in the importance of student independence and the priority of student thinking, we have to ground our classroom discussions in the ideas of our students. Let’s support each other in learning how to turn over the organization and lead of classroom talk to our students, the learners in the classroom.

I’m a big believer in jumping in. We improve in our practice when we try new things. My best advice is to find a shared text or image and turn a whole-class discussion over to the students. Simply tell them that you are going to remain quiet. (It’s harder than it appears.) Open the discussion by asking What are you thinking? and see what happens next.

This work takes bravery (you can’t control what students will say, but it will be organic and honest) and commitment (all good skills require good doses of practice). But there is no doubt about the importance of this instruction. Discussion that deepens the thinking of all participants is an imperative life skill, so let’s start early in letting kids drive the talk.

It helps to videotape the discussion and take a transcript (this will keep you busy and not talking) and use these artifacts to analyze later on your own and with your class. Notice who talks, with what frequency and how the discussion shift the thinking of the group. Consider the role of your voice (or lack of voice). Reflect, set some goals, and try again. If you don’t step back, you don’t know what your students are capable of.

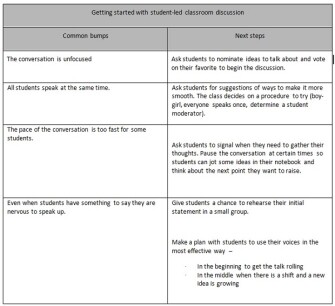

Here are some common bumps that occur when shifting to student-led classroom discussions and some possible next steps that keep the discussion anchored by the thoughts and words of the students. Good luck!

Response From Laura Robb

Laura Robb’s most recent book is Read, Talk, Write: 35 Lessons That Teach Students to Analyze Fiction and Nonfiction:

Face it—our students are social. They adore talking, and they’re great at it! Our challenge is to harness and redirect their talk to thinking about fiction, nonfiction and movie and video clips. So, I’m asking you to step aside and turn over much of the talk to students. In a 45-minute class, teacher talk should add up to no more than 10-12 minutes.

When students are in charge of discussing, they engage in analytical thinking that nudges them to find the language to communicate ideas to peers. Moreover, daily talking about high-quality texts, lessons, words, concepts, and ideas motivates students to listen and learn from each other. With practice, they can become masters of meaningful student-led discussions.

By organizing student-led talk around high-quality texts, students participate in literary conversations. These discussions become complex when students use texts that have multiple layers of meaning. In addition to practicing discussion skills, students need time to reflect on the process, evaluating what worked, what they could improve, and then setting goals for future discussions. Putting reflective self-evaluation into students’ hands nurtures meta-cognition and results in students deciding how to improve their discussions.

Introduce whole-class discussions first because students can practice literary conversation skills while you observe and support them. Once students can demonstrate they can actively listen, maintain the forward motion of their discussion, and use text evidence to support diverse positions, they can transfer these skills to small group or partner discussions.

Student Guidelines

Here are student guidelines for successful student-led discussions:

- Raising hands doesn’t cut it during student-led conversations. Instead, students talk, one at a time, while peers listen and process ideas. Once a student finishes, a peer jumps into the conversation.

- Active listening develops through practice. Active listening means that students concentrate on what the listener is saying and push aside distracting thoughts. Active listeners learn to respect ideas and conclusions that differ from theirs—as long as the text provides adequate evidence for their thinking. Frequently, active listeners paraphrase a peer’s point of view and then offer a different perspective.

- Citing text evidence is important for supporting a position, inference, or connections. Students should encourage each other to cite the text during discussions.

Teacher Guidelines

Here’s how teachers can support student-led discussions:

- Start the discussion with an open-ended question, and then take a back seat and listen and watch.

- Offer students prompts that keep a discussion moving forward. Here are a few: Can you support that with the text? Does anyone have a different idea? How do those ideas connect? Can you explain that term?

- Take notes and summarizes key points to share what you heard and noticed with students.Then ask students to debrief by pointing out what worked and what they could improve on during the next whole-class discussion.

Now, take the plunge and try these suggestions that lead to motivating and engaging student-driven discussions about the content you teach.

1. Guiding Questions. These invite students to ponder an issue that is complex and can apply to different texts. Before you initiate a unit of study, decide on a theme or concept you want students to explore and pose a question that requires deep analysis. For example, 4th graders were investigating self-selected books on natural disasters. Students developed this guiding question: How do natural disasters affect people’s lives? Even though each student read a different book, the question stimulated rich conversations.

2. Interpretive Questions. These open-ended questions have more than one answer and can be text specific. Teach students to pose open-ended questions by inviting groups to develop queries that have at least two different responses. Have students consider verbs that often signal interpretive questions: analyze, examine, compare and contrast, evaluate, show, classify, why.

3. Text Structure. Show students that they can read different fictional texts and link them by discussing text structure. So when 5th graders read different folk tales they can have small group conversations about the protagonist and the problem, forces of good and evil, magic numbers three and seven, the protagonist’s tasks, and the lessons learned.

4. Literary Elements. Model how students can turn literary elements into questions/prompts they can use to explore diverse fictional texts: Who is the protagonist and what are key problems faced? Name several antagonists and show how each one works against the protagonist. Discuss a central conflict and why it was or was not resolved. What are a few important themes? How do other characters view the protagonist? Remind students to always refer to facts and logical inferences in the text to support a position.

5. The Flow of Discussions Avoid the temptation to fix a conversation that stalls for a few seconds. These pauses feel like an eternity. Instead, offer students questions that can restart a discussion and maintain its forward motion: Does anyone see this differently? Can you offer text evidence? What can you add to this theory? Can you explain that term or point? Can you tell more about that idea? Can you clarify that point?

A great benefit of student-led discussions is that they allow you to listen and look at your students in new ways. Ask yourself questions such as: Who is doing most of the talking? Which kids read the same authors or the topics? Who is adept at active listening or posing questions? Which students have natural rapport? Who might I pair that may be in different groups, but I now see will be great discussion partners?

Use these questions and notes you’ve jotted about students to confer with them and provide support that can improve their ability to actively listen and discuss as well as expand their reading interests. Turning discussions over to students and providing them with the tools to make these discussions meaningful and purposeful can develop keen analytical thinkers who use text data to develop and prove their ideas and theories. At the same time, students learn to respect and value interpretations that differ from theirs.

Response From Sky Sweet

Sky Sweet is a candidate for National Board certification at the National Board Resource Center at Stanford. She teaches high school English at the Duncan Polytechnical High School in in Fresno, Calif.:

One of the best classroom discussion methods I’ve recently discovered is the Paideia Seminar. Paideia Seminar is an approach to Socratic seminar that is grounded in the Paideia method of education, which encourages active learning. A Paideia Seminar is a collaborative, intellectual dialogue facilitated with open-ended questions about a text. A text can be something that is a tangible human artifact—such as a poem, a painting, a song, or a science experiment. It’s designed to promote critical and creative thinking. Paideia Seminar shares the essential characteristics of all Socratic dialogue: it is a formal, thoughtful discussion, guided by questions and focused on ideas and values.

What I love about Paideia is the format and structure. There’s a pre-seminar process, seminar questions, and a post-seminar process. As the teacher, it does make for a great deal of front-loading prior to launching a seminar, but the on-going results are worth the efforts. There’s a need to consciously plan the talk-time into the curriculum. But it’s not just talk, it has to be ‘complex talk.’

And that’s where it becomes really interesting for me as the facilitator in the room! I teach primarily English Learners and recently re-designated English Learners—for the most part they are quite shy, reserved, and reluctant to speak in front of their peers. This can make for a very painful Socratic seminar as we all know. But with all the steps, planning, and preparation involved, students know exactly what to expect. They are familiar with a specific text as they’ve read it a few times prior to seminar and they are prepared with highlighted passages and questions in the margins. By focusing on a specific text, Paideia Seminar creates an entry point to engage students with more abstract ideas. Focusing on a text also creates opportunities to explore profound and influential texts within an academic discipline.

On the day of the seminar, there are bullet points on the board with a focus question. The topic question is designed to ask students to relate the discussion topic to their own lives which, again, increases engagement. Students are in a large circle around the room, ground rules are printed on sheets of paper and placed on the floor inside of the circle. Name cards are present on each desk to encourage students to use each other’s names. Students write down a personal goal for that particular seminar on the inside of their name card that they will self-evaluate afterwards. They can choose the way they want to participate which helps with buy-in to the seminar.

Students, not the teacher, are supposed to control the conversation and, with practice, they can do it. Beforehand, a student will volunteer to keep a ‘conversation map’ so that a person maps the conversation visually and leads a debrief with the students afterwards. Students need to talk about ‘how they talk’ and begin to understand the rhetorical devices they are using. Some of the reasons why we have students talk are:

- To access prior knowledge

- share ideas and other’s point of view

- process information

- use of oral language skills

- active learning, more ownership over content

- debate

- metacognition

- to clarify information

- arguing

- develop and respond to an argument

Teaching speaking and listening is a practice. We are introducing these skills to students and exposing them to a bigger idea of what it means to engage in an intellectual conversation. The smaller activities are a means to anchor them in doable tasks that help them to feel secure and enable them to participate even if it’s only one big toe in the water at a time. In a sense, we are helping them establish their intellectual identity and voice—with lots and lots of practice. These are intellectual skills that students need to thrive in today’s society.

Response From Tricia Ebarvia

Since 2001, Tricia Ebarvia has been teaching high school English outside of Philadelphia. She is a co-director for the Pennsylvania Writing & Literature Project and a 2016-18 Heinemann Fellow. Feel free to follow Tricia at triciaebarvia.org or on Twitter @triciaebarvia:

Given today’s contentious social and political climate, the need for civil discourse is critical. How do we respectfully listen to others, especially when we disagree with them? And how do we speak our opinions to others who disagree with us?

This year, I’ve tried to be more deliberate in teaching kids how to have meaningful conversations. One strategy I’m sure most of us have used is the Fishbowl. While there are many variations, the basics come down to this: a small group of students gather in the center of the class—the fishbowl—to discuss a topic as the rest of the class observes and takes notes. After an allotted amount of time, the discussion ends and the entire class debriefs on what went well and how the discussion could be improved.

While I love using the Fishbowl, I notice that students often struggle with knowing how and when to interject. Students get nervous and they may interrupt or jump in with an unrelated point. The key, then, is helping students listen. In her TED Talk, “10 Ways to Have a Better Conversation” Celeste Headlee reminds us of Stephen Covey’s astute observation: “Most of us don’t listen with the intent to understand. We listen with the intent to reply.”

With this in mind, here are three discussion protocols I’ve used that help students practice the skill of listening.

They Say, I Say

Developed by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein, They Say, I Say is a book that focuses on understanding the moves of academic writing. Specifically, Graff and Birkenstein’s work helps students frame their own ideas in response to and in the context of what others say.

I adapted this framework into a discussion protocol. After students read a text, they get into groups for discussion. Student A begins by offering her ideas about the text. Then, moving clockwise, Student B goes next. However, Student B must start by summarizing what Student A has said before saying whether or not he agrees and why. Every time a new student speaks, he must start with what the previous student has said. Therefore, students must actively listen—and accurately restate—what others have said first.

Circular Response

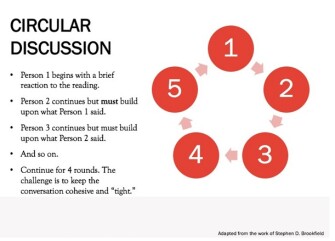

I adapted this protocol from Stephen Brookfield’s book, The Discussion Book: 50 Great Ways to Get People Talking (which I highly recommend!). Like the They Say, I Say protocol, Student A begins by sharing her opinion of the text. Student B must then respond by directly connecting to what Student A has already shared. Then Student C connects to Student B, and so on. Again, students must actively listen. I ask students to try to repeat this process for four rounds, which challenges students to broaden and deepen their conversation. Hint: It’s helpful to have a time limit for each student (30-60 seconds ) to keep the conversation moving.

Designated Listener

During whole group discussion, sometimes it can be hard to keep track of all the ideas that are shared. In this activity, a student is selected (or volunteers to be) the designated listener. During discussion, the designated listener’s job is to take notes. He can do this either at his seat or at the board. If he’s seated, then every five minutes, discussion is paused so that he can quickly recap what’s been said. If he’s at the board, he can “tag” another student to come to the board to continue the notetaking. I keep a class list handy for this activity so that I can cross off students’ names when they’ve had a turn to make sure that everyone has a chance listen actively in this way.

Of course, there are many ways we can encourage active listening, including modeling what it looks like when we teach. If you have any additional ideas, please share.

Response From Patty O’Grady

Patty O’Grady’s work in the field of education and psychology spans 30 years and includes classroom teaching in both K-12 general and special education, as well as higher education, where she is currently a faculty member at the University of Tampa. She is the author of Positive Psychology in the Elementary School Classroom (W. W. Norton and Company; 2013) and is currently working on a book on Mindfulness in Schools (Prufrock Press, 2018):

Build the Five Pillars of Emotional Engagement

The brain is a narrative learner and craves stories with a beginning, a middle, and an end. Every lesson, and ensuing discussion, that begins and ends with a story provokes attention and curiosity. Attention and curiosity are prime brain activators and essential pre-requisites for engaged discussion. Emotional connection to the story creates commitment to the discussion. Emotional learning is indelible learning and emotional discussions are memorable discussion.

Educators who introduce the subject matter as a story about the planets or a story about the election capture student interest and involvement from the start. Educators who introduce the subject matter within the context of a story—the story of the inventor or scientist or author—provoke curiosity.

Stories bring emotional content to learning that illuminates academic content. Stories create meaningful engagement by tapping feelings that are funneled into engaged discussion. Discussion as storytelling, both fact-based and inventive, powers student engagement and motivation to remember, understand, connect, analyze, synthesize, evaluate, and share the lesson in their own words and within the sphere of their own experience.

I once observed a teacher present the life cycle of a plant as a story of a tree that personalized the content and activated cognition. The story prompted students to tell their own stories of trees climbed, trees planted, and trees cut down. Students remember and are enthused to discuss what is important in their own consequential encounters.

Discussion is especially evocative and successful when educators build the three pillars that support emotion-based, engaged discussion:

- Trust

- Educators trust their students to extract relevant content from storytelling and to share their own content-related emotional experiences. Students trust the teacher, and each other, to share their own content-related stories with partners, small groups, or whole class. Trust enables discussions that enhance knowledge, understandings, and broaden perspective through animated, honest dialogue. Relationship is the 1st pillar of engaged discussion.

- Challenge - Educators assure the subject is not mundane or inconsequential. Problems, events, issues, and more, derived from the content and connected to authentic learning promote emotional engagement. After a history lesson about Native Americans who returned to defend their land facing certain death, a teacher asked her students: ‘What is worth dying for?’ Provocative thought is the second pillar of engaged discussion.

- Wonder - Educators bring the wonder. They include not only the ‘what’, ‘where’, and ‘when’ (the facts)—most importantly—they include the ‘how’ and ‘why’. Wonder enchants emotion and wondering why and how are at the core of engaged discussion. Questions, possibilities, ideas, inventions, inquiry, discovery—both factual and fanciful—are encouraged and distinguished. Growth mindset is the outcome of wondering when a student is fully engaged in discussion. Growth mindset is the ability to open one’s mind to a new and different viewpoint. Wonder that opens minds is the third pillar of engaged discussion.

Think about the last time you told a story with an embedded lesson at dinner. If told well, it is likely that you captured the imagination of all listening and prompted their related stories. Engaged, meaningful, enlightening discussions do not happen because you gather a group of students together and assign a topic. Engaged discussion is prepared like a grand meal—carefully, thoughtfully, and with plenty of stories consumed at the table. The recipe for engaged discussion is one part positive relationship and two parts inviting challenge—mixed with a pinch of wonder.

Thanks to Kara, Laura, Sky, Tricia, and Patty for their contributions!

Please feel free to leave a comment with your reactions to the topic or directly to anything that has been said in this post.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at lferlazzo@epe.org. When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo.

Anyone whose question is selected for this weekly column can choose one free book from a number of education publishers.

Education Week has published a collection of posts from this blog, along with new material, in an e-book form. It’s titled Classroom Management Q&As: Expert Strategies for Teaching.

Just a reminder—you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email or RSS Reader. And, if you missed any of the highlights from the first six years of this blog, you can see a categorized list below. They don’t include ones from this current year, but you can find them by clicking on the “answers” category found in the sidebar.

This Year’s Most Popular Q&A Posts

Best Ways To Begin The School Year

Best Ways To End The School Year

Student Motivation & Social Emotional Learning

Teaching English Language Learners

Entering The Teaching Profession

I am also creating a Twitter list including all contributers to this column.

Look for Part Three in a few days..

Save