What have we learned from the last two years of MOOC research that could help improve the design of courses?

This post continues my series of short posts on seven general themes from MOOC research that could inform the design of large-scale learning environments in the years ahead.

- MOOC students are diverse, but trend towards auto-didacts (July 2)

- MOOC students value flexibility, but benefit when they engage frequently (July 6)

- The best predictor of persistence and completion is intention, though every activity predicts every other activity (July 12)

- MOOC students (tell us they) leave because they get busy with other things, but we may be able to help them stay on track (July 16)

- Students learn more from doing than watching (Today!)

- Lots of student learning activities are happening beyond our observation: including note-taking, socializing, and using other references

- Improving student learning outcomes will require measuring learning, experimenting with different approaches, and baking research into courses from the beginning

5. Students learn more from doing than watching

Imagine two possible approaches to building a production shop for Massive Open Online Courses. One approach makes a major investment in video production, and that shop hires lots of editors, videographers, and producers, and only uses the basic assessment and discussion features available through the MOOC platform. A second approach focuses on developing interactive activities, and that shop hires people with really programming chops. They create videos by having instructors do very simple screencasts or lectures. If you have limited resources to invest in people and approaches, I’d recommend the second approach.

Ken Koedinger and colleague from Carnegie Mellon University published a great paper at Learning@Scale called “Learning is not a Spectator Sport: Doing is Better than Watching for Learning in a MOOC.” He compared students who did activities in a MOOC with students who watched videos, and he found that students who did activities outperformed those who did not, even those who watched lots of videos. Despite the heavy investment and emphasis on video in many MOOCs, students need to do stuff to learn.

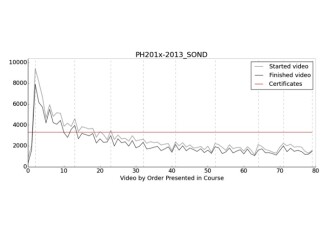

We also know empirically that in many courses, video watching behaviors drop off over the course of a course. Below are two figures, from a HarvardX U.S. Health Policy course and from a Coursera course on Data Visualization. Both show the same pattern. By the end of the course, many students are not watching the videos. In fact, in many (but not all) courses, the number of video watchers is below the number of certificate earners by mid-way through the course. Put another way, plenty of the people who earn a certificate in a course are not watching the videos by the end. Interviews with students suggest that they are reading transcripts from the videos or listening to audio downloads, instead.

(From IVMOOC: http://cns.iu.edu/2015-MOOCVis.html)

There is very little evidence to support the value of investments in high-production video. There doesn’t seem to be much correlation between the quality of video production and registration numbers--there are courses with very simple videos that have gotten large numbers of registrants, and courses with highly produced videos with limited enrollment. There is limited evidence that students prefer screencast videos with pen interactions that talking over slides alone, though I think there is no evidence comparing screencasts to on-location videos, animations, or other more sophisticated approaches. There is no evidence about the quality of the correlation between video quality and learning outcomes. For MOOC shops making big investments in high quality video, I just don’t see the evidence justifying that investment.

Course developers allocating scarce resources should consider carefully the utility of video, especially videos produced for the later weeks of a course. It may be that students learn more from activities and experiences than videos. I’m particularly interested in those activities, like simulations, formative peer assessment, and synchronous online discussion, that create learning experiences that students might not have in other contexts. When MOOC producers do invest in video, I’d encourage the bulk of that investment going into the very first few videos. Substantial more students watch the first few videos in a course than subsequent ones. I’d encourage video producers to focus most heavily on those opportunities to reach the majority of a course’s students.

For regular updates, follow me on Twitter at @bjfr and for my publications, C.V., and online portfolio, visit EdTechResearcher.